Surrender of Japan

Soviet invasion of Manchuria. Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

6 August - 2 September 1945

The situation that beckoned General Douglas MacArthur, Admiral Chester Nimitz and General George Marshall’s operations planning staff at the Pentagon was an unenviable one. They had to consider a Japan that by any rational criteria was defeated, but which was not only refusing to surrender but seemed to be preparing to defend the soil of her mainland. Few doubted that Operation Olympic – a strike against Kyushu slated for November 1945 – and Operation Coronet, an amphibious assault in March 1946 against the Tokyo plain on Honshu, would lead to horrific loss of Allied life on the ground.

1 of 4

Estimates of expected casualty rates differed from planning staff to planning staff, but over the coming months – perhaps years – of fighting, anything in the region of 250,000 American casualties were thought to be possible. ‘If the conflict had continued for even a few weeks longer,’ believes historian Max Hastings, ‘more people of all nations – especially Japan – would have lost their lives than perished at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.’

2 of 4

MacArthur was designated supreme commander for Olympic, the invasion of Japan scheduled to commence with a landing on Kyushu. Meanwhile, the Allied bombers continued to incinerate the enemy’s cities, and Japanese industrial production approached collapse. The US Third Fleet under Halsey closed in on Japan and began its own intensive program of carrier air strikes against the mainland, inflicting carnage and destruction upon areas that had escaped the attentions of Twentieth Air Force. ‘In the forefront of the invader, his great carrier task force rampaged about … like a mighty typhoon,’ wrote naval officer Yoshida Mitsuru in awed frustration.

3 of 4

Objectively, it was plain to the Allies that Japan’s defeat was inevitable, for both military and economic reasons, and thus that the use of atomic weapons was unnecessary. But the prospect of being obliged to continue addressing pockets of fanatical resistance all over Asia for months, if not years, was appalling. Experience, especially at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, showed that the enemy exploited every day of grace to strengthen his defenses, and thus to raise the cost of delaying invasion. The chiefs of staff were also concerned that the American people’s patience with the war was ebbing, and thus that it was essential to hasten a closure in the east.

4 of 4

While these preparations for Olympic were going forward, another major Allied offensive was being planned for Southeast Asia. As the campaign in Burma was ending in the largest Allied victory over the Japanese army in World War II, the British looked toward the reconquest of Singapore.

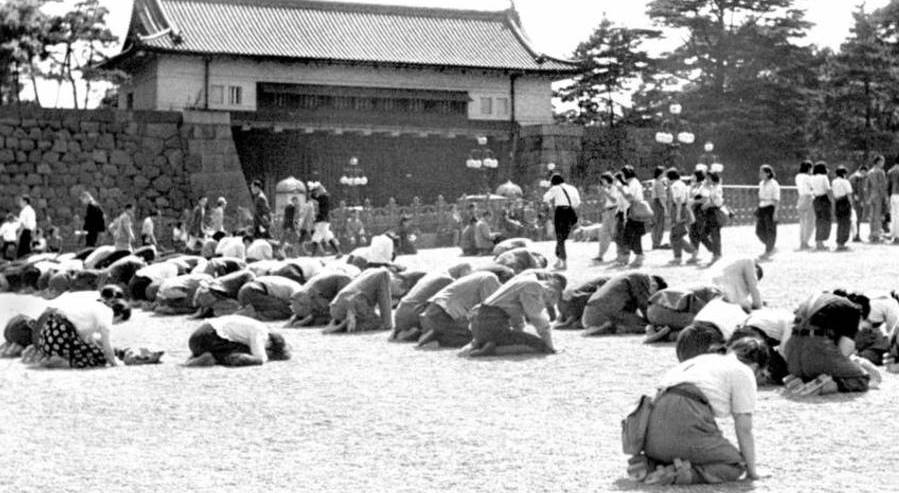

In spite of fears to the contrary, the occupation proceeded peacefully. Japan had been battered by bombing and isolated from what remained of her empire by the destruction of most of her shipping by submarines and mines. However, it had not been fought over inch by inch, and the vast majority of her soldiers and sailors would survive to come home and share in the rebuilding of a damaged but not devastated country. The occupation lasted until 1951 when the San Francisco Peace Treaty was signed by 48 nations. The treaty came into effect on April 28 1952, and restored sovereignty to Japan, with the exception - until 1972 - of the Ryukyu Islands.

1 of 2

The existing government structure would be simultaneously kept and remade, its personnel utilized and purged. The Americans arrived not to conquer but to reform. They planned to transform Japanese society, and in many ways they succeeded so well that the Japanese came to maintain many of the changes then made, long after the American occupation had ended.

2 of 2

Whatever the subsequent taboos in Japan about that country's role in initiating and conducting the Pacific War, in Japan after World War II, unlike Germany after World War I, no one ever came to doubt that the country had indeed been defeated — and without what President Truman had called ‘an Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other.’

Battle of Iwo Jima

During the Battle of Iwo Jima American marines landed on the island of Iwo Jima and eventually captured it from the Japanese Army.

Battle of Okinawa

During the last stage of the war against Japan, the US invaded the Japanese island of Okinawa. The fierce japanese resistance convinced the American policymakers to make use of the Manhattan Project's atomic bombs and not to invade the main Japanese islands.

Borneo Campaign

During the last stages of the Pacific War, Australian forces organized a series of landings on the island of Borneo. The goal of the campaign was the liberation of the island from Japanese hands.

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War: A new history of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011

- Max Hastings, Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2007