East Prussia Campaign

First battles on the Eastern Front

17 August - 14 September 1914

The Russian invasion of Eastern Prussia occurred on the Eastern Front of World War One. The offensive was a means of diverting German troops from the Western Front to the Eastern Front of the Great War, thus providing indirect support to the British and French forces. In the end, despite the fact that they had superiority in numbers over the Germans, the Russians were defeated in the battles of Tannenberg and Masurian Lakes.

1 of 5

Under French pressure, and out of a genuine desire to do its best by the western allies against the common German enemy, the Russian High Command in 1914 was committed to do its part. Two-fifths of the peacetime army were in any case stationed around the great military centre of Warsaw, from which its strategic deployment against East Prussia and the Carpathians might easily be achieved. The reception there of reinforcements from the reserves mobilized in the interior was also a simple matter.

2 of 5

Given Germany's anticipated weakness in the east, Russian staff calculated that sufficient force could be found to mount an offensive on the East Prussian frontier that would ensure a crisis for Berlin in its backyard, which was also the historic homeland of the German officer corps. Thus an attack through Masuria toward Königsberg and the other strongholds of the Teutonic Knights from which the Germans sprang would be certain to create acute material and psychological anxiety in the German High Command.

3 of 5

Geography was to disrupt the smooth onset of the Russian combined offensive. Less excusably, timidity and incompetence were to disjoint it in time. In short, the Russians repeated the mistake made so often before by armies apparently enjoying an incontestable superiority in numbers: that of exposing themselves to defeat in detail, that is, of allowing a weaker enemy to concentrate at first against one part of the army, then against the other, and so beat both.

4 of 5

Though the Russians knew that they outnumbered the Germans, their means of identifying the enemy's location were defective. The Russian cavalry, despite its large numbers, did not seek to penetrate deep into the enemy positions, but preferred to dismount and form a firing line when it encountered resistance.

5 of 5

While the aviation service of the Russian army was the second largest in Europe with 244 aircraft, aerial reconnaissance completely failed to detect German movements. The German 2nd Aircraft Battalion, however, together with the two airships based at Posen and Königsberg, began to report both the strength and the march direction of the Russian columns as early as a week before they began to cross the frontier. Aircraft and airships would continue to provide vital information throughout the campaign.

The Russian Army was a huge beast. Even though the reservoir for conscription was largely restricted to the Russian Christian population, and multifarious reasons were justification for exemption, the empire was so huge that the standing army of 1.4 million would reach 5 million on mobilization. Their training had been rudimentary, concentrating on basic soldierly skills. Yet in some areas, the Russian Army was surprisingly innovative, with a large Imperial Air Service and much experimentation ongoing into the possibilities of armored cars. Yet many of these new weapons were not yet operational.

1 of 7

Individual conscripts served three years in the infantry on call up, then seven years in the reserve, followed by eight years in the second-class reserve, before a final period in the militia until they reached the age of forty-three. In 1914, the mobilization plans were greatly sped up by a combination of preparatory measures and the French-financed improvements to the railway system, which allowed the Russians to place 2 million men ready for action on the Eastern Front within thirty days.

2 of 7

The Russian officer corps was also distinctly variable in quality. The top was rife with personal animosities, professional jealousies, factionalism and regional parochialism. Many officers had also been distracted by extensive counter-insurgency duties in the aftermath of the 1905 Revolution, while others were swamped by paperwork or thwarted by the innate conservatism of many of their superiors. Another dragging factor on the efficiency of the Russian Army was the illiteracy of the vast majority of the lower ranks, a result of the poor Russian educational system.

3 of 7

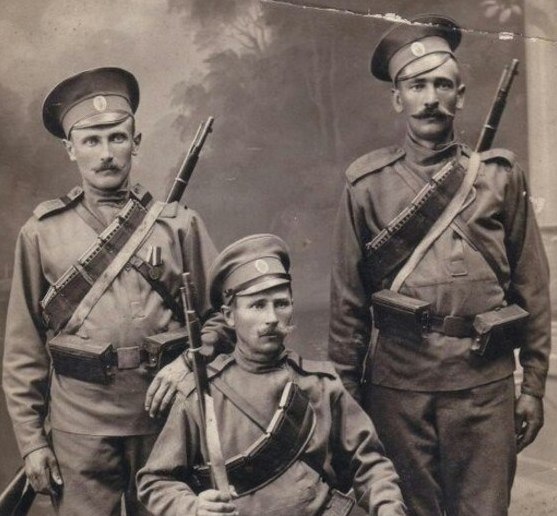

The Russian Army was better equipped than is sometimes imagined, with the standard rifle being the magazine bolt-action Mosin-Nagant rifle, which was a reliable and accurate weapon. The infantry regiments were further equipped with eight machine guns of the belt-fed water-cooled Maxim M1910 type, which proved to be both efficient and practical in action. Like the British and German infantry, the Russian soldier wore a camouflage uniform, a greenish khaki which came in many different shades, especially after heavy wear.

4 of 7

The main field gun, the Putilov 76.2 mm, was a fine weapon, while the heavier 122 mm and 152 mm Schneider guns were the main heavy artillery – although, as with most armies, there was a severe shortage.

5 of 7

Shortages would become apparent during mobilization and even more so when the fighting began: rifle and machine gun ammunition, shells and, frustratingly, many basic items of equipment and uniform, including an inexplicable dearth of boots – surely an easily calculable essential. The problems of the Army were deep set within the state, since Russia was still a backward, primitive society which could only ever harvest a small proportion of its huge assets even in the case of war. This was just as well for the Central Powers, for Russia’s population outnumbered that of Germany and Austria-Hungary combined.

6 of 7

There were human defects also. Russian regimental officers were unmonied by definition and often poorly educated; any aspiring young officer whose parents could support the cost went to the staff academy and was lost to regimental duty, without necessarily becoming thereby efficient at staff work.

7 of 7

The qualities of the peasant soldier — brave, loyal and obedient — traditionally compensated for the mistakes and omissions of his superiors. But face to face with the armies of countries from which illiteracy had disappeared, as in Russia it was far from doing, the Russian infantryman was at an increasing disadvantage. He was easily disheartened by setback, particularly in the face of superior artillery, and would surrender easily and without shame, en masse, if he felt abandoned or betrayed. The trinity of Tsar, Church, and country still had the power to evoke unthinking courage; but defeat, and drink, could rapidly rot devotion to the regiment's colors and icons.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Hew Strachan, The First World War: To Arms (Volume I ), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Norman Stone, The Eastern Front 1914-1917, Penguin Books, London, 1998