Battle of Galicia

Austro-Hungarian defeat in Galicia

23 August - 11 September 1914

The Battle of Galicia, also known as the Battle of Lemberg, was fought between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires on the Eastern Front of World War One. During the battle, the Russians defeated the Austro-Hungarians and captured the city of Lemberg, today known as Lviv and located in western Ukraine. The Austro-Hungarians were forced out of Galicia and for almost nine months the Russians ruled Eastern Galicia, until their defeat during the Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive.

1 of 3

Due to confusion over choice of priorities between the fronts in Galicia and Serbia, the Austrians were slower to concentrate their forces against Russia than they should have been. Meanwhile the Russians, defying the German and Austrian staff estimations, were quicker. Their enemies had not made allowance for the fact that two-fifths of Russia's peacetime strength was stationed in the Polish salient, or for the eventuality that Stavka (Russian GHQ) would push the troops in Poland forward before general mobilization had been completed. It was a crucial difference in attitude.

2 of 3

The Russian victory illustrated a dilemma that would plague Stavka throughout the war. German forces were closer to Russia's vital centers than the Austro-Hungarian troops, and Germany was the main enemy. Austria-Hungary's weaker forces could be contained or beaten with a relatively small proportion of Russia's, and the rest used against Germany. But it was also arguable that Germany could not survive alone, so there were two schools of thought among Russia's generals, one giving priority to Germany, the other to the 'soft underbelly', Austria-Hungary.

3 of 3

From the beginning, the Austro-Hungarian forces in Galicia were bedevilled, not only by delays, but also by a fundamental uncertainty as to what they were meant to achieve. They were supposed to attack. But to attack from the semi-circle of Galicia was difficult: if they attacked on the western side, their eastern flank would be increasingly bared; yet if the attack went to the east, it would run into all manner of difficulties. Railways were few; roads, on the Russian side, few; the Germans far away.

Facing the Russians was the Austro-Hungarian Army. In peacetime it numbered some 440,000 men, but on mobilization would expand to a more intimidating 3.35 million, deployed in forty divisions. Yet this was another state that had neither the internal cohesion nor the modernized infrastructure to capitalize on its huge size. With a population of around 50 million, it was the third most populous state in Europe in 1914, but it had no concept of nationhood; here was a country ready to be torn apart by local nationalism.

1 of 6

The infantry conscripts were called up at eighteen years of age and served two years before passing on to ten years in the Landwehr reserve, followed by a further period with the inactive Landsturm until they were fifty-five years old. Overall their standard of training was basic.

2 of 6

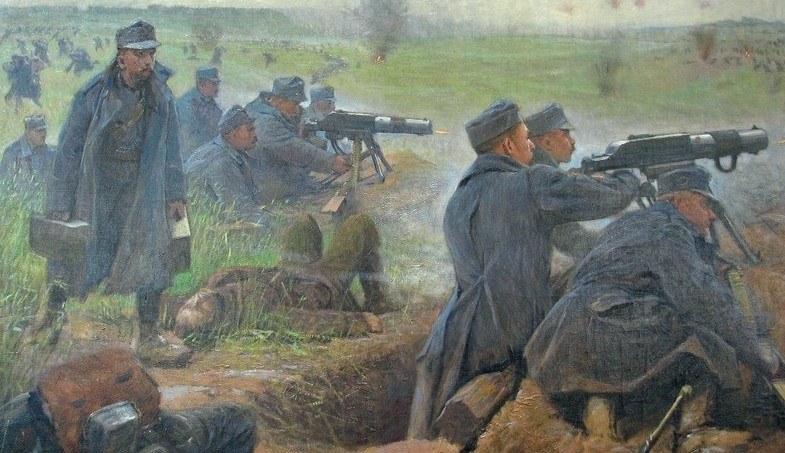

Dressed in a light blue uniform, the Austro-Hungarians were armed with the bolt-action magazine Mannlicher M1895 rifle, which was both reliable and capable of extremely high rates of fire: up to thirty-five rounds a minute. Austrian machine gun companies tended to have four sections, each armed with two water-cooled Schwartzlose M.07/12, guns which had the advantage of being significantly lighter than their competitors’, although at the cost of some loss of range and penetrating power.

3 of 6

The artillery was functional with a high proportion of mountain guns of various calibers. Unlike most countries, Austria had developed some formidable heavy artillery typified by the Skoda 305 mm 1911 siege howitzer. This beast had a crew of at least fifteen and was towed by a 15-ton motorized tractor. Eight Skodas would be lent to the Germans to assist in the reduction of the Belgian forts on the Western Front in August 1914. The Austrians had similar expertise in the manufacture of powerful – and deadly – mortars.

4 of 6

Austria's principal emotional, if not rational, war aim, however, remained the punishment of Serbia, which had precipitated the July crisis by its involvement in the Sarajevo assassinations. Sense would have argued that Austria should deploy its whole strength forward of the Carpathians to engage the Russians, the Serbs' protectors. Outrage and decades of provocation demanded the defeat of the Belgrade government and the upstart Karadjordjevic dynasty.

5 of 6

The Austro-Hungarian General Staff agreed that, in the event of two-front war, Germany’s most sensible course would be to concentrate against France in the first round; consequently, Austria-Hungary would have to undertake a large part of the work in the east, until German troops could come from France.

6 of 6

Formally, the Austro-Hungarian plan before 1914 was for a full-scale offensive against Russia; formally, too, there was an undertaking on the Germans’ part that VIII Army would, if possible, contribute a parallel offensive from East Prussia. The Austro-Hungarian chief of staff dreamed of expelling the Russians from Poland, and was confident enough, when war broke out, to appoint an Austro-Hungarian governor of Warsaw.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Norman Stone, The Eastern Front 1914-1917, Penguin Books, London, 1998