Brusilov Offensive

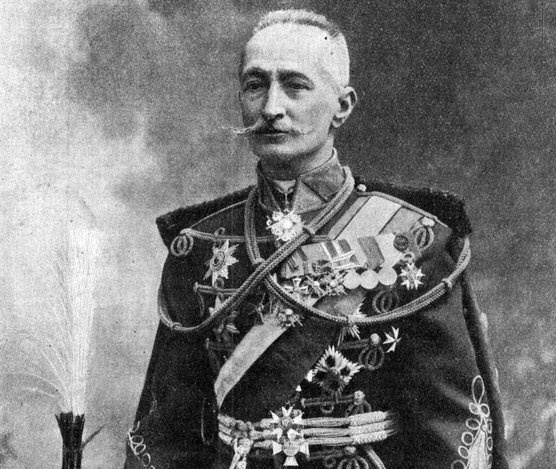

General Alexei Brusilov attacks Austro-Hungarian positions using new tactics

4 June - 20 September 1916

The Brusilov Offensive was undertaken by the Russian Army against the Central Powers on the Eastern Front of World War One. It was one of the worst crises faced by the Austro-Hungarian Empire during the war. The battle took place in what is today western Ukraine, in the area adjacent to the towns of Lviv, Lutsk and Kovel. The offensive was named after the Russian general who planned it, Alexei Brusilov, commander of the Southwest Front.

1 of 4

Brusilov’s tactical innovations marked a new level of military best practice for 1916. As such they would be closely studied by the armies of all the major combatants.

2 of 4

Brusilov believed victory against the weakened Austrians was possible through careful preparation, and since he requested no reinforcements, he was given permission to make his attempt.

3 of 4

When the offensive opened, two questions were crucial: Did the Austrians know what to expect? and How would the troops perform? The answer to the first soon became clear: they did not. The second question had less simple answers. Most troops performed well, but there was a worrying desertion rate. Thus, during three weeks of inactivity and four of a successful offensive, enough men for three full-strength divisions deserted.

4 of 4

The Russian armies north of the Pripet Marshes also went on the offensive, profiting from Brusilov's success, to press forward toward Baranavichy, the town where the Russian headquarters had previously been located. This offensive, opposed by German troops, was soon stopped but Brusilov's army group sustained its success over the Austrians throughout the summer.

The military problems of the First World War consisted of a number of circles to be squared. A successful offensive needed both surprise and preparation. These were incompatible: preparation of millions of men and horses took so long that surprise was impossible. In the same way, mobility and weight could not be reconciled. A huge weight of guns could be assembled. The enemy might be defeated. Then the guns could not be moved forward. In other words, armies would be mobile only if they did not have the weight to make their mobility worthwhile. Brusilov and his staff were the first to try to find solutions to these problems.

1 of 4

Brusilov’s staff noted that, in a breakthrough operation, there were two main problems: the breakthrough itself, and the exploitation of it. These demanded almost contradictory solutions. A breakthrough could only, it seemed, be achieved by assembly of great weight. But assembling this weight of guns and shells would mean that the enemy knew what to expect, and when. The defence would know where to put reserve troops. Consequently, even if the breakthrough were achieved, the attackers would stumble onto a new line. Counterattacks would follow; enemy artillery would enfilade the attackers in the area of breakthrough and the attack would collapse, despite its initial tactical success.

2 of 4

Most often this method of attack had failed during the war. Most recently, at Lake Naroch, the Russians had failed with these methods. Of these failures, various interpretations were possible. On the southwestern front, the view was taken, by Brusilov though not by some of his subordinates, that the breakthrough operation had failed precisely because strength had been too narrowly concentrated.

3 of 4

The essential difficulty was that attackers were not sufficiently mobile. In the circumstances, there seemed no solution at all except ‘attrition’ — to attack the enemy where he could be hit hardest, where he would be obliged to fight, i.e. his strongest point — and then make him lose many thousands of men by heavy bombardment. This was the method chosen by Falkenhayn in the summer of 1915, and executed particularly by Mackensen. This was also chosen on the Western Front by the Germans at Verdun, and by the Entente on the Somme.

4 of 4

Most commanders preferred to believe that the breakthrough operations had failed for a variety of other causes — not enough shell

in particular; reserves not moved into support fast enough; troops lacking in ‘elan’, and so on. Each of these had sufficient validity to be convincing to many experienced observers. But they were far from being the whole truth.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Norman Stone, The Eastern Front 1914-1917, Penguin Books, London, 1998