Battle of Verdun

Germany wants to weaken the French Army to the point of exhaustion

21 February - 18 December 1916

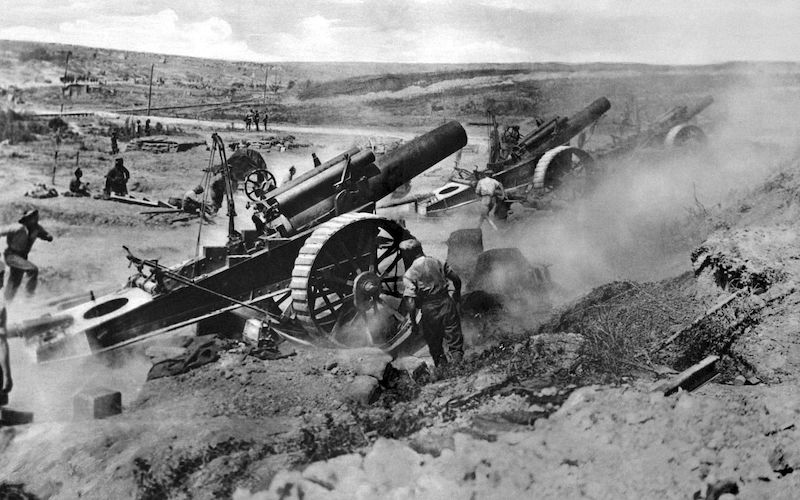

The battle of Verdun was the largest battle of the Western Front of World War I fought between the French and German armies. The fighting lasted for 303 days, and it remains one of the bloodiest battles in human history. During the battle, the Germans attacked the French army in the Verdun area. At first the Germans had some success, capturing Fort Douaumont and Fort Vaux. But as the battle progressed the Germans had to redirect troops from the Verdun area to the battle of the Somme. In the final phase of the battle, the French managed to recapture much of the lost ground, including Forts Douaumont and Vaux.

1 of 6

The balance of power on the Western Front was changing, because although the Germans had strengthened their forces in the west after their successful campaigns on the Eastern Front, the BEF was also expanding. It now had around a million men under arms – a total of thirty-eight infantry divisions and still growing. Nevertheless the French remained the dominant ally, with some ninety-six divisions under the command of General Joseph Joffre in January 1916.

2 of 6

There was no denying that the French had borne the brunt of the war on the Western Front since August 1914. By comparison, the British contribution had been negligible: those battles in which they had been involved, such as Neuve Chapelle or Loos, barely registered as skirmishes when compared to the titanic clashes in the Artois and Champagne.

3 of 6

Amidst all the mayhem and destruction, the sophistication of the bombardment had also taken a step forward with the widespread use of gas shells on battery positions, to suppress the fire of the French guns during the German attack across No Man’s Land.

4 of 6

Almost encircled by ridges and hills on both banks of the Meuse, Verdun was also protected by rings of forts. The strongest, in theory, was Fort Douaumont, perched on a 1,200-foot height located to the north-east of the city, on the right bank. However, the strength of the forts was illusory. Many of their guns had been removed to provide extra firepower for the French autumn operations of the previous year.

5 of 6

After the initial French debacles, General Philippe Petain, known for his pragmatism, would probably have preferred to implement a controlled withdrawal. However, as an unambitious officer who shunned intrigue and ostentation, Petain was ideally suited to the role in which he was now cast. He understood modern firepower and was trusted by his troops. His very presence at Verdun lifted morale and he inspired renewed confidence in the Verdun forts as the backbone of a 'Line of Resistance'. French artillery was concentrated to give the Germans a taste of attrition.

6 of 6

In planning the Verdun offensive, the German General Staff had undoubtedly been aware that once summer arrived, they could expect Entente offensive operations to commence on many different fronts, including the Western Front. The German General Staff basically had no reserves. Once an offensive began somewhere else, it could be stemmed only by the diversion of resources. So far, the Germans had been able to use their still substantial superiority in firepower to compensate. But the guns, like the men, would have to be diverted when the next offensive began.

In December 1915 it had been decided that there would be a huge Anglo-French offensive on the Western Front to coincide with simultaneous offensives by the Russians and the Italians. Joffre had selected the Somme area where the British and French would fight side by side. This was alliance warfare and Douglas Haig, the British Expeditionary Force commander, was left with no option but to comply if the union was to survive and prosper. Yet neither Joffre nor Haig would have the chance to dictate what was about to happen on the Western Front. At the start of 1916 the French position at Verdun was not healthy.

1 of 4

The new year saw a new team at the heart of the British military. In London, General Sir William Robertson had been appointed as Chief of Imperial General Staff. General Sir Douglas Haig had been promoted to command the BEF. The two would work in harmony, united in their belief that the prevailing strategic situation meant that the bulk of British resources should be devoted to fighting the main enemy – Germany – in the deciding theatre of war, the Western Front.

2 of 4

From the British perspective, the Ypres salient was the more obvious sector from which to attack, not least because it was closest to the Channel ports and the British Expeditionary Force’s supply lines. But militarily Britain was the junior partner of the coalition. French’s replacement by Haig promised an improvement in Anglo-French relations. When Haig met Joffre in February 1916 he readily agreed that the attack should be in Picardy, astride the River Somme, where the two armies met.

3 of 4

A generally quiet sector since 1914, the great fortress at Verdun had been denuded of most of its guns during the desperate combing out of heavy artillery for the autumn offensives of 1915. The whole sector was only defended by four divisions and two brigades of Territorial troops. There had been a definite complacency at Joffre’s headquarters despite warnings as to the inadequacy of the French defences.

4 of 4

The advent of a period of heavy snow and rain on the date of the originally intended attack militated against the effective deployment of the German artillery that was essential to the success of the attack. It forced a 9-day postponement. These precious few days allowed the French the chance to realise what was about to happen and belatedly to concentrate their forces. By the time the Germans attacked, the French had eight divisions and over 600 guns on the east and west banks of the Meuse.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003