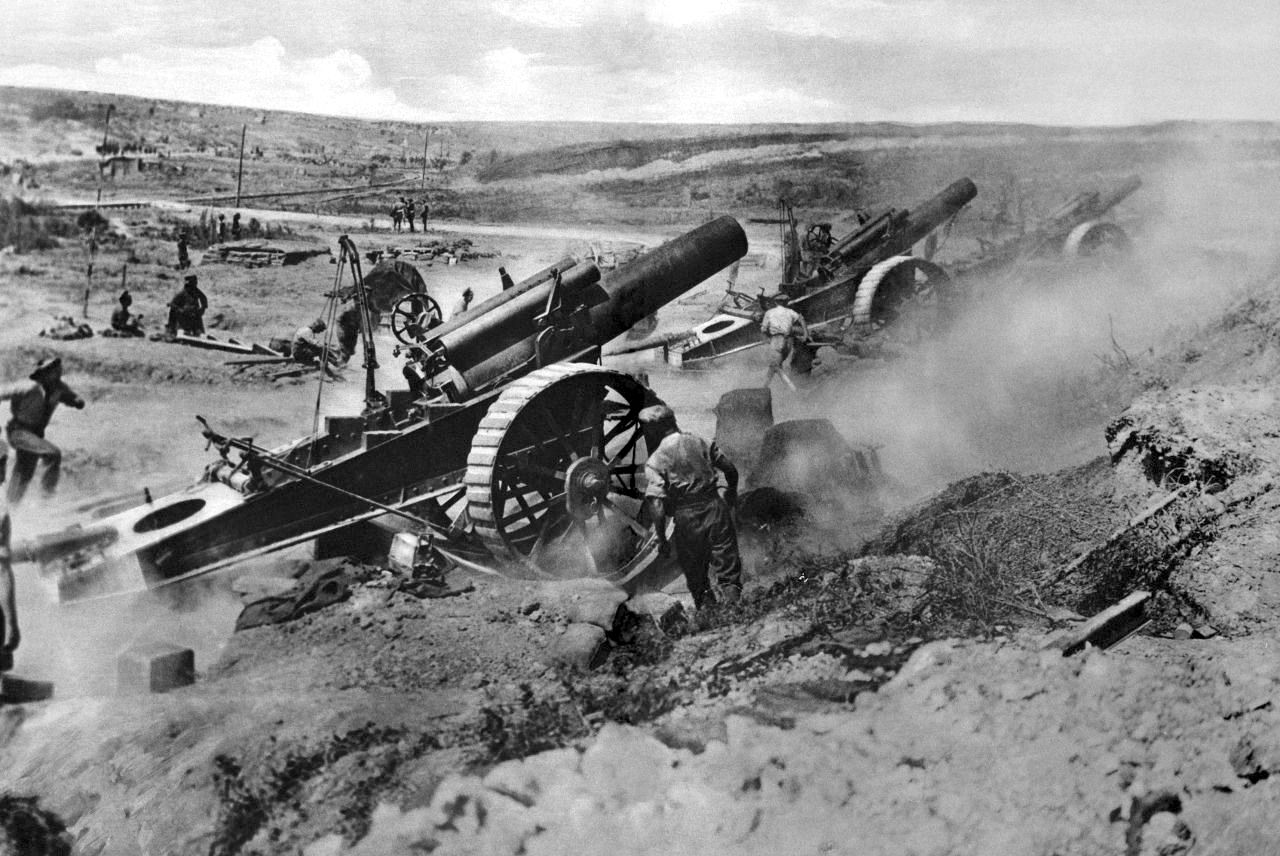

Battle of the Somme

The Entene forces attack the German Army on the river Somme

1 July - 18 November 1916

The Battle of the Somme, or the Somme Offensive, was fought during World War I on the Western Front. The battle was drawn between the Anglo-French forces of the Entente on one side, and the German Empire on the other. It took place on both sides of the river Somme, in France. More than one million men were wounded or killed during the battle, making it one of the bloodiest in history. At the end of the battle, the British and French had penetrated some 10 km into German occupied territory, taking more ground than in any of their previous offensives since 1914. However the Germans held their ground at Péronne and Bapaume, where they spent the following winter.

1 of 3

The choice of the Somme region in Picardy for the Franco-British offensive was largely determined by the fact that it marked the junction of the French and British forces. Its drawbacks were that no great strategic objectives, such as rail centers, lay close behind the German front. Also, because the sector had long been quiet, the Germans had constructed formidable defences in the Somme chalk.

2 of 3

The demands of Verdun had reduced the French contribution to the Somme assault to only 11 divisions. For the first time in the war, the British would therefore play the leading role in an Entente offensive on the Western Front.

3 of 3

In the high summer of 1916, operations on the Somme seemed to offer the front line troops nothing but unending sacrifice. With the slogging match at Verdun already in its fifth month, there could be no question of halting the Somme offensive.

The sheer size of the commitment demanded by the Battle of Verdun soon derailed any thoughts of the French Army making the major contribution to the planned offensive on the Somme. Instead, General Joseph Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief, exerted increasing pressure on Douglas Haig, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, to launch a British-led offensive as early as possible. Haig preferred to delay as he recognized that many of his new divisions would need time to evolve into a powerful attacking force. Yet Joffre was desperate and Haig had little option but to accept a start date of the 1st of July 1916.

1 of 2

Much has been written about what Haig was trying to achieve on the Somme, but his intentions seem clear enough: ‘My policy is briefly to: 1. Train my divisions, and to collect as much ammunition and as many guns as possible. 2. To make arrangements to support the French … attacking in order to draw off pressure from Verdun, when the French consider the military situation demands it. 3. But while attacking to help our Allies, not to think that we can for a certainty destroy the power of Germany this year. So in our attacks we must also aim at improving our positions with a view to making sure of the result of the campaign next year.’ (General Sir Douglas Haig, General Headquarters, BEF)

2 of 2

By this time Haig had settled his General Headquarters in the small château of Montreuil. There has been much criticism speculating on the life of luxury supposedly led by the ‘château generals’. But the GHQ was in itself a large organization of staff officers which required space and an excellent communications system if it was to function properly. Haig and his staff certainly had a stern and unwavering work ethic: ‘Punctually at 8.25 each morning Haig’s bedroom door opened and he walked downstairs. He then went for a short 4 minutes’ walk in the garden. At 8.30 precisely he came into the mess for breakfast. If he had a guest present, he always insisted on serving the guest before he helped himself. He talked very little, and generally confined himself to asking his personal staff what their plans were for the day. At nine o’clock he went into his study and worked until eleven or half past. At half-past eleven he saw army commanders, the heads of departments at General Headquarters, and others whom he might desire to see. At 1 o’clock he had lunch, which only lasted half an hour, and then he either motored or rode to the headquarters of some army or corps or division. Generally when returning from these visits he would arrange for his horse to meet the car so that he could travel the last 3 or 4 miles on horseback. When not motoring he always rode in the afternoon, accompanied by an aide de camp and his escort of 17th Lancers, without which he never went out for a ride. Always on the return journey from his ride he would stop about 3 miles from home and hand his horse over to a groom and walk back to headquarters. On arrival there he would go straight up to his room, have a bath, do his physical exercises and then change into slacks. From then until dinner time at 8 o’clock he would sit at his desk and work, but he was always available if any of his staff or guests wished to see him. He never objected to interruptions at this hour. At 8 o’clock he dined. After dinner, which lasted about an hour, he returned to his room and worked until a quarter to 11.’ (Brigadier General John Charteris, General Headquarters, BEF)

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998