Battle of the Frontiers

First battles of the World War One

14 - 24 August 1914

The Battle of the Frontiers was the gigantic clash that would make or break the hopes of both Germany and France. The two great competing visions of the war – the latest versions of the Schlieffen Plan and the French Plan XVII – were put to the ultimate test, moving at long last from theory to practice. The battles were fought along the Eastern French border and in South Belgium. In the end the Franco-British forces were driven back, allowing the German forces to invade Northern France.

1 of 6

There was the very distinct possibility of mutual failure in the fog of war, where the vagaries of chance melded with incompetence, and the unforeseen activities of opposing forces could thwart the most enterprising of commanders.

2 of 6

The tragic outcome was evident for all to see. French casualties during these failed offensives exceeded 200,000, of which over 75,000 were dead in just a few days of desperate fighting. The Battle of the Frontiers was not just a disaster for the French Army; it was a disaster for the whole French nation.

3 of 6

Belgium was squarely in the center of the target. The Belgians already knew that in the event of a conflict, if they let the Germans pass through their country, it would promptly be appropriated in one way or another by France or by Great Britain. Conversely, if they refused, they would have to face Germany.

4 of 6

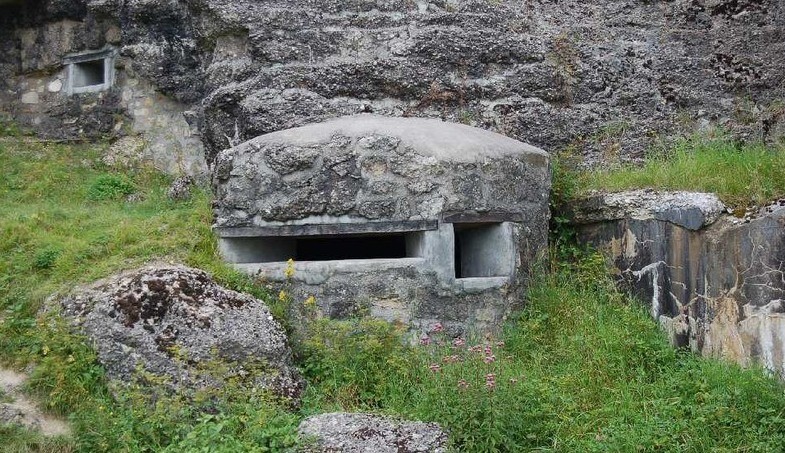

The Belgian forts, like the French ones, had been designed as part of an integrated defense system, so Belgium’s twenty-four thousand infantry, with their field guns, were a key component of the defense. The forts themselves had no infantry. All they could do was fire their guns to prohibit the German advance.

5 of 6

The French had counted on the fact that the difficulty of taking Liège and Namur was such that the Germans would stay to the south of

those strong points in their violation of Belgium. In the event they didn’t, the French estimated that it would take the Germans a great deal of time to reduce the Belgian forts. The key mistake was not the failure to recognize that the Germans would move through Belgium, but a wildly optimistic estimate of the capabilities of the defenders.

6 of 6

French troops moving slowly up into Belgium were told that the Germans were in terrible shape and had run out of food, and that the Belgians were winning. Wartime propagandists claimed that twenty-five thousand Germans were killed and wounded in the assault on Fort Barchon alone. Tales quickly circulated, allegedly from eyewitnesses, about human wave attacks by Teutonic hordes driven on by sadistic officers. So the French and British who first encountered the Germans were completely unprepared for what hit them: not waves of men, but waves of howitzer shells.

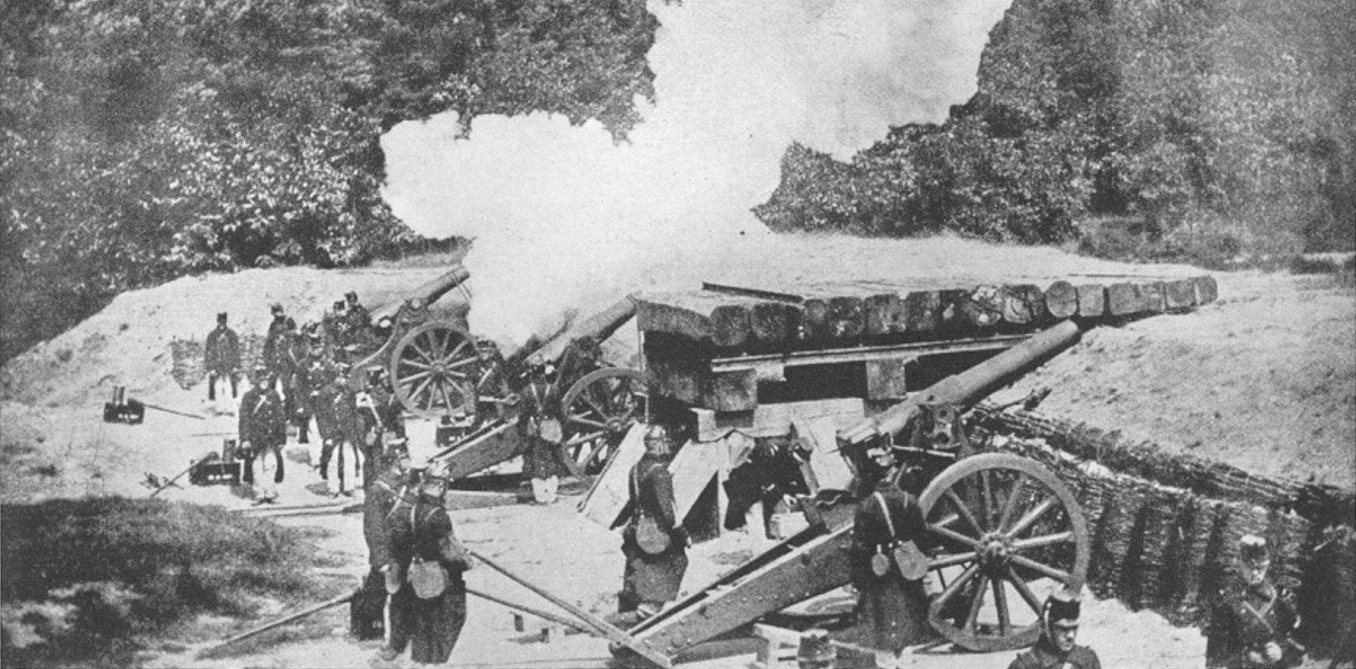

The German Army was a professional body that took war very seriously. The German main thrust, which would ultimately set the agenda, was the advance of the First and Second Armies across the Belgian border and deep into northern France. The neighboring Third Army would also pass through the Belgian Ardennes. The Fourth and Fifth Armies would advance through Luxembourg and the French Ardennes. This meant that effectively all five armies would be performing a gargantuan wheeling manoeuvre to overwhelm the French left flank. Meanwhile, the German Sixth and Seventh Armies would stand fast in Alsace-Lorraine.

1 of 6

The tools for the German plans were yielded by mobilization, which swelled the Army’s strength from 754,000 in peacetime to a rather more imposing 2,292,000. The reservists were recalled to the colors to be organised into seventy-nine divisions, of which sixty-eight were to be deployed on the Western Front.

2 of 6

As far as was humanly possible, the German Army was ready for war, superbly equipped and diligently trained over the years of peace. The infantry was armed with the Mauser Gewehr 98, a magazine bolt-action rifle which was an accurate weapon capable of a reasonable speed of fire.

3 of 6

The German soldier was drilled to be capable not only of individual accuracy but also of concentrating fire, in a squad or platoon, on to identified targets to maximise the impact. Each infantry regiment also had a machine gun company of six Maxim machine guns which could be utilised together to lay down an intense concentration of fire both in defence and in support of an attack.

4 of 6

German attack tactics emphasized the importance of winning the firefight before launching the attack in open order, with tightly controlled short bounds, the men dropping to the ground as required before finally over-running the enemy position and preparing for a possible counter-attack. All these functions were rehearsed on large training areas spread across Germany. These were the kind of exercises that were impossible to implement in more densely populated France or more parsimonious Britain and Russia.

5 of 6

The problem for the Germans with developing an attack through Belgium was the near-continuous belt of forest that dropped down into France and ran parallel to the Meuse, beginning as the Ardennes and ending up as the Argonne. There was only a small area in which to attack along the Meuse. German armies would have to march in an arc to attack on the western side of the forest.

6 of 6

The strength of the Belgian forts had alarmed the German generals. They were, indeed, immensely strong, subterranean and self-contained, surrounded by a ditch thirty feet deep. Infantry assault upon them was certain to fail. Their thick skins would have to be broken by aimed artillery fire, and quickly, for a delay at the Meuse crossings would throw into jeopardy the smooth evolution of the Schlieffen Plan. Yet Liège had to be taken. Such was the necessity, and such the urgency, that the German war plan provided for the detachment of a special task force from Second Army to complete the mission.

World War One - the Spark

World War I was sparked by the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, the Austrian heir to the throne, by a Bosnian Serb. This event triggered an international crisis that led to the outbreak of the Great War.

Battle of Mons

At Mons the British Expeditionary Force tried to hold their ground against the German onslaught into Belgium. Although the British inflicted more casualties on the Germans than they suffered themselves, they were eventually forced to retreat due to the numerical and tactical superiority of the Germans and the retreat of the French Fifth Army.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Hew Strachan, The First World War: To Arms (Volume I), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998