Battle of Stalingrad

Germany and its allies are defeated by Russia at Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad, modern-day Volgograd, took place between the Soviet Union and the Axis forces. The battle is often cited as one of the turning points of the war. The fighting took place in three major stages: the German assault of the city, the battle inside the city, and the Soviet counter-offensive. The last phase captured and destroyed the 6th German army in the city.

1 of 7

Hitler and the Wehrmacht High Command were forced to take several factors into account when they chose their objectives for the campaign of the summer of 1942. The losses suffered by the German army during the Moscow campaign constituted the principal factor. At the end of the Soviet counter-offensive, the German army had around 162 divisions on the eastern front, of which only 8 could fulfil offensive missions. The armored units were not in a good situation, since the 16 armored divisions had only 140 functioning tanks.

2 of 7

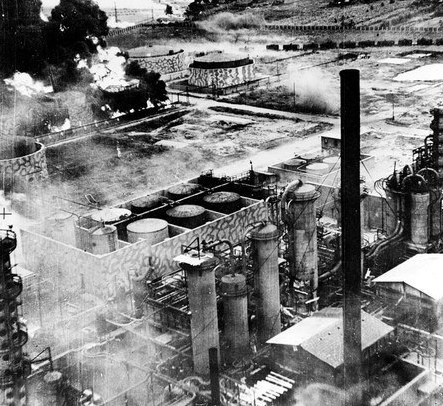

In order to support a long war, Germany urgently needed consistent economic resources, especially oil. “Black gold” is indispensable for carrying out modern warfare, in which tanks and planes occupy pole position. The Reich was repeatedly confronted with perspectives of depleted oil supplies, in spite of deliveries from Romania.

3 of 7

The attention of the OKW, and implicitly of Hitler, turned towards the rich oil deposits in the Caucasus. If he could conquer them, his needs would be satisfied, and his enemy would be deprived of a source of fuel vital for the continuation of the war. The Soviet Union would also lose the rich basin of the Don river. Furthermore, a victory would offer the Germans the possibility of occupying Iraq and eliminating the British presence in the Middle East.

4 of 7

In this stage of the war, the Red Army was much less capable of carrying out mobile operations than the Wehrmacht. It was only the perspective of an urban war that reduced the Russian disadvantage compared with the German forces. This kind of war was dominated by artillery and infantry battles to the detriment of mechanized tactics.

5 of 7

After the defeat in Moscow, during the spring of 1942, the German forces stabilized the front. They began to be confident that they could defeat the Red Army as soon as the cold weather passed. The Central Army Group was involved in tough battles during the winter campaign, however 65% of the infantry of this group did not take part in the fighting, so the soldiers were rested and re-equipped. This was what gave the Germans confidence.

6 of 7

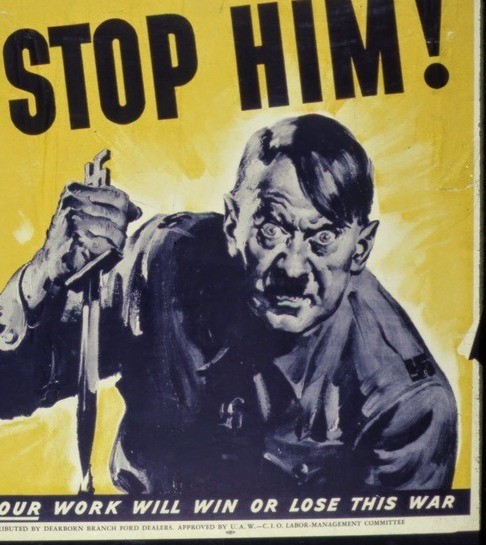

From a military perspective, the capture of Stalingrad was important to Hitler for two reasons. First of all, it was a major industrial city on the Volga river, a vital transport route between the Caspian Sea and northern Russia. In the second place, capturing the city would ensure the safety of the left flank of the German armies. Thus, he could advance towards the rich oil fields of the Caucasus region. At the same time, the capture of this city could be used for propaganda purposes. Aware of all these things, Stalin ordered general mobilization. Everyone who could hold a weapon was sent to defend the city.

7 of 7

The Germans’ desire to conquer the important industrial city of Stalingrad was understandable. Once the city was conquered, the oil terminal at Astrahan was at their fingertips. The Russians would no longer be able to use the Volga for transport. Further, the Army Group A in the Caucasus would be sheltered from another Soviet winter offensive. In these conditions, attacks from the north could begin again. At that moment, the conquering of the city seemed to be justified from a military perspective.

The Army Group Center was chosen to advance in the Caucasus region and capture the oil resources in that area. The plan for this summer offensive was called Fall Blau or Case Blue. The plan included elements from the 6th Army, 17th Army, 4th Panzer Army and 1st Panzer Army. Hitler ordered the Army Group South to be divided into two. The Army Group South ‘A’, under the command of Wilhelm List, had the task of advancing south, towards the Caucasus region. Group ‘B’, made up of the 6th Army of Friedrich von Paulus and the 4th Panzer Army, advanced towards Volga with Stalingrad as their objective.

1 of 7

Some German and Romanian units which were to participate in Fall Blau were still caught up in the siege of Sevastopol. Thus, the start of operations was postponed by approx. one month. After the end of operations in this sector, the Axis units were redirected towards the objectives of Case Blue. In the initial plans of Operation Barbarossa, the city of Stalingrad was not even mentioned. However, Moscow and Leningrad were still resisting, and the Soviets had launched a counteroffensive. As a consequence, Stalingrad began to take form in Hitler’s plans

2 of 7

Hitler’s strategic concepts, also sent to the OKW, were concretized in the famous Directive No. 41 which defined the objectives of the German campaign. This document occupies a special place in the history of World War II. Directive No. 41 was at the foundation of the Wehrmacht’s involvement in the Battle of Stalingrad, one of the bloodiest conflicts of the entire war. The document foresaw retaking the strategic initiative lost after the battle for Moscow and beginning an offensive in the southern sector of the front.

3 of 7

The goal of the German offensive was to “wipe out the entire defense potential remaining to the Soviets, and to cut them off, as far as possible, from their most important centers of war industry.” Due to the losses suffered in the previous winter’s campaign, the Wehrmacht was forced to limit its offensive effort to the southern sector of the eastern front. There, the German forces would be concentrated with the mission of “destroying the enemy before the Don, in order to secure the Caucasian oilfields and the passes through the Caucasus mountains themselves.”

4 of 7

The plan elaborated by the OKW, based on the directive, foresaw the execution of two parallel blows. The first would be carried out in the Kharkov sector, along the right-hand bank of the Don River towards Stalingrad; the second in the Rostov direction. Later, after crossing the Don, the offensive would continue in the direction of the Caucasus. A fundamental principle concerning the planned operations was their execution in successive stages.

5 of 7

Directive No. 41 foresaw the carrying out of two preliminary operations with the goal of ensuring the safety of the flanks of the groups attacking in the Caucasus. The conquest of Crimea and the capture of Sevastopol were carried out with the goal of ensuring the safety of the western flank. For the security of the eastern flank, it was necessary to occupy Voronezh and go down the Don, and also attack Stalingrad.

6 of 7

The main objective of the campaign was the Caucasus with its oil fields, according to the analysis of the directive. Stalingrad was initially just a secondary objective, however the evolution of hostilities transformed it into a principal one. The German plan had two fundamental errors. In the first place, the OKW didn’t take account of the obvious disproportion between their objectives and their available means. Secondly, the main objective, the Caucasus, was outside the center of the front. As a consequence, the front line became excessively long, and thus the Wehrmacht’s attack capability was weakened.

7 of 7

The plan did not meet with unanimity in the German Command. During debates in the OKW, several military commanders spoke for giving up the idea of starting a new offensive campaign in the USSR. These men insisted that the existing front line must be maintained and even shortened. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt requested a retreat in Poland, and General Franz Halder proposed “rectification” of the front line. This would allow the German army to consolidate the positions attained and create a moving force able to repel any attack.

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the codename for the invasion of the Soviet Union by the Axis forces. The operation was named after Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, the leader of the Holy Roman Empire, one of the leaders of the 12th century crusades.

Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk, codenamed Operation Zitadelle - Citadelle - was the last great Blitzkrieg offensive on the eastern front. To this day, the battle remains the greatest tank conflict in the history of mankind.

- John MacDonald, Great Battles of World War Two, Michael Joseph Books, London, 1986

- William Craig, Enemy at the gates: The battle for Stalingrad, Penguin Books, New York, 1973

- Christer Bergström, Stalingrad – The Air Battle: 1942 through January 1943, Chevron Publishing Limited, Crowborough (England), 2007

- Antony Beevor, Stalingrad, Penguin Books, London, 1999

- S.S. Joel Hayward, Stopped at Stalingrad: The Luftwaffe and Hitler’s defeat in the East 1942-1943 (Modern War Studies), University Press of Kansas, Kansas, 1998

- Otmar Trașcă, Catastrofa de la Stalingrad și consecințele sale, 1942-1943

- Andrew Roberts, Furtuna războiului, O nouă istorie a celui de-al Doilea Război Mondial, Litera, București, 2013

- Gabriela Pantiș