Battle of Midway

'Midway was the most crucial battle of the Pacific War, ... made everything else possible’ - Admiral Chester W. Nimitz

4-7 June 1942

The Battle of Midway was a decisive naval conflict between the forces of the United States and Imperial Japan during World War Two. The battle occurred in the Pacific Theater of the war. The US Navy defended against the attacking Japanese fleet, inflicting damage that could never be repaired. After Midway, Japan’s capacity to replace losses became insufficient in the context of an escalating conflict. Meanwhile, the rapid growth of the US industry meant that America was able to replenish her forces far faster. Midway, along with the subsequent Guadalcanal Campaign, is often cited as a turning point in the Pacific War.

1 of 7

Rear-Admiral Frank Fletcher said: ‘After a battle is over, people talk a lot about how the decisions were methodically reached, but actually there’s always a hell of a lot of groping around.’ This was vividly demonstrated by the Coral Sea engagement; despite the US intelligence’s magnificent achievement of pinpointing Midway as the next Japanese objective, uncertainty and chance also characterized the battle.

2 of 7

Once the Americans had figured out the correct sequence of the intended Japanese moves in the South and Central Pacific on the basis of careful and successful signals intelligence, they collected their remaining three usable carriers in the Pacific and provided them with what screening force was available. With the two modern battleships North Carolina and Washington in the Atlantic, nothing larger than cruisers could be employed. Unknown to the Japanese, the three carriers were sent out to meet them.

3 of 7

The Japanese carriers sent their first strike against Midway, but the Midway commander was determined not to be caught with his planes on the ground. The bombs dropped by Midway planes on the Japanese all missed; but the damage caused by the raid on the island, though considerable, was not considered sufficient by the Japanese to prepare the way for the landing assault. A second air attack on the island was ordered, but from here on things began to go wrong.

4 of 7

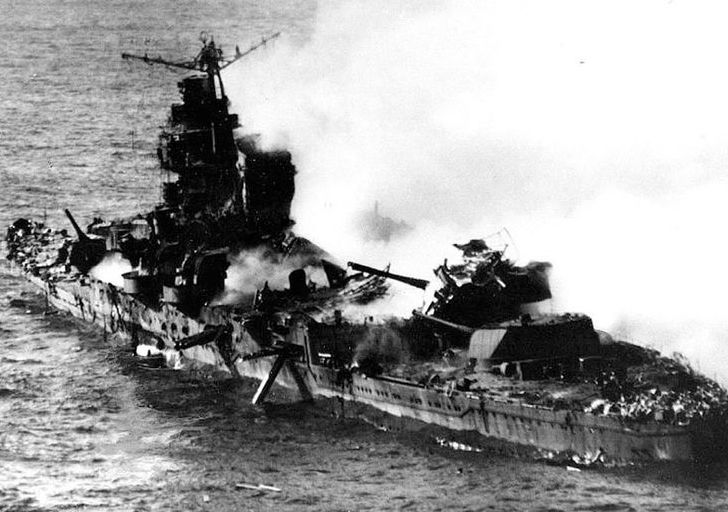

The Japanese had to change the arming on the planes kept on their carriers for the second strike. Then they received reconnaissance reports that there were American warships soon identified as carriers in the area and therefore once again altered the arming of their planes for this contingency. This made them extremely vulnerable when the Americans attacked their fleet because fuel hoses, armed planes, and ammunition were all over the hangar and flight decks: the result was a carnage that devastated the Japanese fleet, which lost all four of its carriers.

5 of 7

The American loss of the Yorktown was soon offset by the return of the repaired carrier Saratoga to the fleet at about the time the Japanese had refitted the Zuikaku with a new group of airplanes; but the fundamental fact was that there was no way for the Japanese to replace within a reasonable time the four carriers they had lost.

6 of 7

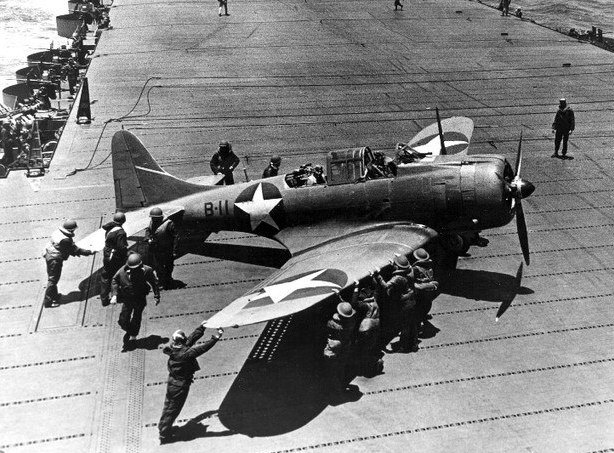

After Midway, the US Navy had a new fighter on the way, the F6F Hellcat, which it tested successfully against a captured Japanese Zero, prised intact from the Aleutian tundra where it had crashed in June 1942. Not only would new carriers soon arrive in the Pacific, but they would carry new-model fighters, scout dive-bombers, and torpedo planes that would match the best Japanese aircraft. In the meantime, pilot experience and prudent tactics would have to suffice.

7 of 7

The Battle of Midway represented the high mark of Japan’s geographic expansion, but not a major change in the strategy of seize-and hold. Shaken by the loss of four carriers and 100 invaluable pilots, the Japanese admirals however still controlled a balanced fleet with excellence in gunnery, night fighting, and ordnance that surpassed the US Navy. The four carriers could be replaced — as they were in 1944 — but the temporary material and psychological setback for the IJN offered the Allies an opportunity to take the strategic initiative.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto split his invading force into three, which was an error as it caused the squadrons to be too far apart to support one another. As well as Chūichi Nagumo’s First Air Fleet, there was a Midway Occupation Force carrying 51,000 men, and his own main force comprising one carrier, four cruisers, seven battleships, twelve destroyers and eighteen submarines. As well as taking Midway, Yamamoto was hoping to lure the American Pacific Fleet into a massive engagement that, in hindsight, it could not win.

1 of 6

Admiral Yamamoto strove with all the urgency that characterized his strategic vision to force a big engagement. Less than a month after the bungled Coral Sea action, he launched his strike against Midway atoll, committing 145 warships to an ambitious, complex operation intended to split the US forces. A Japanese fleet would advance north against the Aleutians, while the main thrust was made at Midway. This would provide a diversion to confuse the Americans: because of its assault on American territory it might coax the American navy into battle; and in the end it would provide bases for blocking any American attacks on the Kuriles and the Japanese home islands from Alaska. It ended up doing none of these things.

2 of 6

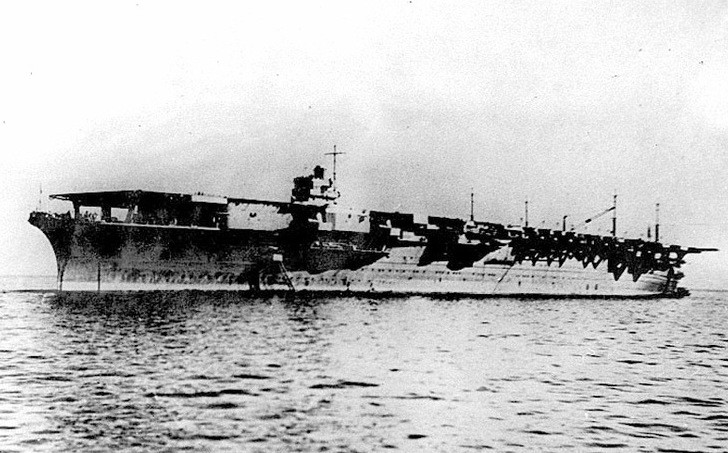

Nagumo’s four fleet carriers – Zuikaku and Shokaku were left behind after their Coral Sea mauling – would approach the island from the north-west, with Yamamoto’s fast battleships three hundred miles behind; a flotilla of transports, carrying troops to execute the landing, would close from the south-west.

3 of 6

How Nagumo was to cope with the Midway base and the American navy if involved with both simultaneously had never been clarified, since honest answers to those officers who raised the question would have required that the whole plan were abandoned or severely modified. It was, however, precisely this contingency which arose.

4 of 6

The great advantage with which the Japanese had begun at Pearl Harbor was dwindling. Nevertheless, the Japanese were confident that Midway Island could be neutralized by carrier strikes and then seized, with the American fleet being destroyed soon after. All questions raised within the naval staffs were brushed aside; Japanese experience and superiority would suffice to cope with all contingencies.

5 of 6

Yamamoto may have been a clever man and a sympathetic personality, but the epic clumsiness of the Midway plan emphasized his shortcomings. It required him to divide his strength; worse, it reflected characteristic Japanese hubris, by discounting even the possibility of American foreknowledge.

6 of 6

The Japanese would enjoy a three-to-two aircraft advantage, which would have been even worse had not Pearl Harbor’s repair crews put Yorktown back into minimal working order. Japanese Navy commanders had every reason to believe they would finish the destruction of the US Pacific Fleet that they had begun at Pearl Harbor.

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War: A new history of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Max Hastings, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939-45, HarperCollins Publishers, London 2011