Battle of France

Germany invades the Low Countries and France

The Battle of France, known as ‘The Fall of France’ took place in World War II, when German forces invaded the Low Countries and France. The battle was made up of two main operations. During ‘Fall Gelb’ or Case Yellow, German mechanized units pushed through the Ardennes to surround the Allied units stationed in Belgium. The second operation, ‘Fall Rot’ or Case Red, involved flanking the Allied forces along the Maginot Line, and an advance made by the German armed forces into French territory.

1 of 7

Between the invasion of Poland and the battles in western Europe, there was a period of combat inaction between the Allies and Germany. This period is also known as ‘The Phoney War’. During this period, Hitler made an offer of peace to both western Allies. The British refused Hitler’s proposal and, a few days later, the French did the same.

2 of 7

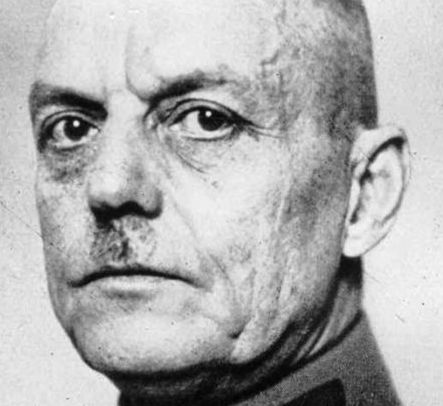

Franz Halder, the German chief of staff, came up with the first project for a frontal attack on France. According to this project, Germany must sacrifice almost half a million soldiers. Hitler was very disappointed by Halder’s plan, because he hoped to rapidly occupy Benelux. Halder’s plan made this impossible. Thus, Hitler decided that the German forces, whether ready or not, should attack early, in the hope that the Allies were not prepared for war. Thus, the attack date was set for only a few weeks after the invasion of Poland.

3 of 7

The initial date for an attack on France was later cancelled. Hitler was persuaded by his generals that the German armed forces were not yet prepared. Hitler gave his generals the task of improving the war plan so that a rapid victory would be possible. Halder’s plan was not met with approval from General Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of Army Group A. In contrast to Hitler, von Rundstedt, a career military man, understood perfectly how the plan must be modified.

4 of 7

General von Manstein was no longer involved, and Franz Halder was the one who had to implement the changes. The new plan had the advantage of being unpredictable for the Allied defensive. The plan stipulated that the principal German forces should cross the Ardennes, an area with many forests and a very poor network of roads. Thus, the element of surprise could be created.

5 of 7

For a quarter of a century there was a generally accepted hypothesis concerning France. According to this, the plan to destroy France in World War I failed because, between the initial conception of the plan and its implementation, too many troops were withdrawn from the strong right flank, which was ahead, and placed on the weaker left flank. The plan to destroy France was drawn up by Alfred von Schlieffen and put into practice nine years after its conception.

6 of 7

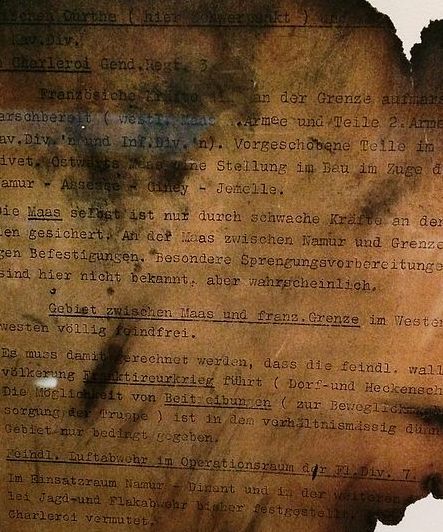

After the New Year, a German airplane made a forced landing in Belgium. One of the passengers on the plane was Major Hellmuth Reinberger, who was carrying a copy of the German war plans. Although the plane landed safely, the major didn’t manage to destroy the documents in time, and they arrived in Belgian hands. Thus, the Germans had to make a drastic change in plan. The change occurred when General Erich von Manstein presented his plans to Hitler. Hitler was so impressed that the very next day he ordered the plans to be changed in line with von Manstein’s ideas.

7 of 7

For the plan to work, it was essential that the Allied forces be attracted towards the north, to defend Belgium. For this to happen, Army Group B had to carry out a static attack, similar to those used in World War I, on Belgium and Holland. Thus, the impression was given that this was the main German force. At the same time, Army Group A would carry out an attack of encirclement through the Ardennes region.

Hitler was later given credit for Manstein’s new plan. Keitel described the Führer as ‘the greatest field marshal of all time’. Even six years later, he confessed to his psychiatrist in Nuremberg: ‘I thought he was a genius. Many times he displayed brilliance… He changed plans – and correctly for the Holland-Belgium campaign. He had a remarkable memory – knew the ships of every fleet in the world.’ Keitel regularly told the Führer himself that he was a genius. Nazi propaganda made Hitler into what he wasn’t: a great military strategist.

1 of 4

At the time, Dr. Goebbels’ propaganda was transmitting the message that Hitler was ‘the greatest warlord of all time’, but Hitler at least knew that it was state propaganda. The fact that he was constantly being told the same thing by his own chief of staff could only tickle his huge pride.

2 of 4

It is true that Hitler had a phenomenal memory of the technical details of any sort of weaponry. From his library, which initially was made up of 16,300 books, 1,200 volumes can be found in the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. These include almanacs about military vessels, military planes and armored vehicles. ‘There are exhaustive works on uniforms, weapons, supply, mobilization, the building-up of armies in peacetime, morale and ballistics, and quite obviously Hitler has read many of them from cover to cover,’

wrote the Berlin correspondent of United Press International.

3 of 4

Hitler’s actual knowledge of military issues was certainly surprising. This has impressed some modern apologists, such as Alan Clark and David Irving. The former affirmed: ‘His capacity for mastering detail, his sense of history, his retentive memory, his strategic vision – all these had flaws, but considered in the cold light of objective military history, they were brilliant nonetheless.’

4 of 4

The moments in which Hitler showed interest for technical issues concerning weaponry during the war are countless. When he wasn’t asking about specific issues in the ‘Führer Conferences’ with top OKW figures and military commanders, nothing gave him more pleasure than showing off his detailed knowledge of these things. Even so, knowing the caliber of a weapon or the tonnage of a ship is far from having the genius of a strategist. Keitel confused the two, an unforgivable error for someone in his role and with his responsibilities.

Operation Weserübung, Invasion of Denmark and Norway

Operation Weserübung was the codename for the German plan to invade Norway and Denmark.

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain was an aerial battle which took place during the Second World War. The British Royal Air Force (RAF) defended the island of Great Britain from the Luftwaffe, the German Air Force.

- Martin Marix Evans, The fall of France: Act with daring, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2000

- Gerhard L. Weinberg , A World at Arms: A Blobal History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995

- A.J.P.Taylor and S.L.Mayer, A history of world war two, Octopus Books, London, 1974

- H. Friezer, The blitzkrieg legend: The 1940 campaign in the west, Naval Institute Press,Annapolis (United States), 2005

- Andrew Roberts, Furtuna războiului, O nouă istorie a celui de-al Doilea Război Mondial, Litera, București, 2013

- Gabriela Pantiș