Battle of Caporetto

German-Austrian forces defeat the Italian Army

24 October - 19 November 1917

The Battle of Caporetto, also known as the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, was fought between Italy and the combined forces of Germany and Austria-Hungary on the Italian Front of World War One. During the battle the Austro-Hungarians, reinforced by their German allies, were able to break through the Italian lines and rout the enemy forces opposing them.

1 of 3

On the Italian Front, as everywhere else, it was evident that the Austrians desperately needed support from the Germans; unfortunately for the Italians, they got it.

2 of 3

The German general Erich Ludendorff recognized that an Austrian political and military collapse could follow a 12th battle of the Isonzo, so he sent massive reinforcements. These included elite German units trained in new tactics, in which assault troops, called ‘storm troops’, advanced rapidly, by-passed centers of resistance and struck at the enemy's headquarters and gun lines. In one such unit was an officer with a future: Major Erwin Rommel commanded a company in a Wurttemberg mountain battalion that was to play a key role in the forthcoming battle.

3 of 3

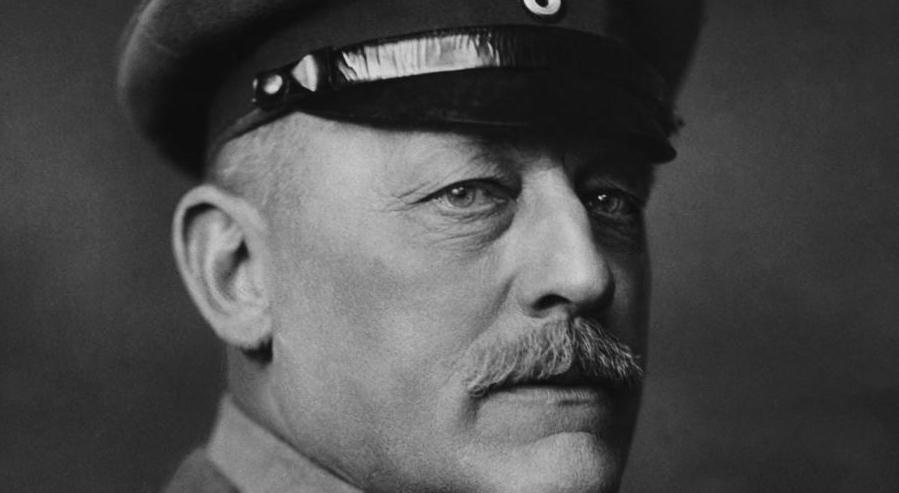

The newly formed 14th Austro-German Army came close to winning the campaign outright. Its commander was General Otto von Below, who had an outstanding record of victories already to his credit. The Austro-German offensive was prepared with a meticulousness that the Italian Supreme Command could hardly imagine. The execution, too, was incomparably efficient.

Ludendorff was only willing to supply German troops for offensive operations, not just to shore up the line, which he considered to be a waste of his valuable resources. The collapse of the Russians on the Eastern Front had given him a last chance to bring the war to a close. His plan was to knock Italy out of the war prior to the great assault he had planned for the Western Front in 1918.

1 of 7

Ludendorff also had in mind another experiment with the assault tactics so effectively trialled by General Oskar von Hutier’s Eighth Army at Riga on the Eastern Front in September 1917. This time he brought in General Otto von Below to command the composite German-Austro-Hungarian Fourteenth Army (consisting of seven German and a number of Austrian divisions). Inserted into the line in the Upper Isonzo sector facing the town of Caporetto, this formidably well-trained force was to spearhead the whole attack. Von Below made their priorities absolutely clear: ‘The ruling principle for any offensive in the mountains is the conquest and holding of the crests, in order to get to the next objective by these land bridges. Even roundabout ways on the crests are to be preferred to the crossing of valleys and deep gorges, as the latter course takes longer and entails greater exertions. The valleys are to be used for the rapid bringing up of closed reserves, the field artillery and supply units. Every column on the heights must move forward without hesitation; by so doing opportunities will arise to help a neighbor who cannot get on, by swinging round in rear of the enemy opposing him.’

2 of 7

Emperor Karl wrote to the Kaiser ‘in faithful friendship’. The Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo ‘has led me to believe we should fare worse in a twelfth’. Austria wished to take the offensive, and would be grateful if Germany could replace Austrian divisions in the east and lend him artillery, ‘especially heavy batteries’. He did not ask for direct German participation; indeed he excluded it, for fear of cooling the Austrian troops’ rage against ‘the ancestral foe’. The Kaiser replied curtly and referred the request to Ludendorff. The German general staff had already assessed that the Austrians would be broken by the next Italian offensive. If Austria-Hungary collapsed, as it probably would, Germany would be alone: an outcome that had to be prevented.

3 of 7

Paul von Hindenburg, the Chief of the General Staff, sent one of his most able officers to reconnoitre the ground. An expert in mountain warfare, Lieutenant General Krafft von Dellmensingen had served in the Dolomites in 1915 and seen the emergence of fast-moving assault tactics against Romania. He now prepared a plan to drive the Italian Second Army some 40 km back from the Isonzo to the Tagliamento and perhaps beyond, depending on the breakthrough and its collateral impact on the lower Isonzo.

4 of 7

The attack, in and of itself, was not intended as a fatal blow; the Germans believed the Italians were so dependent on British and French coal, ore and grain that nothing short of total occupation – which was out of the question – could make them sue for peace. Success would be measured by Italy’s inability to attack again before the following spring or summer.

5 of 7

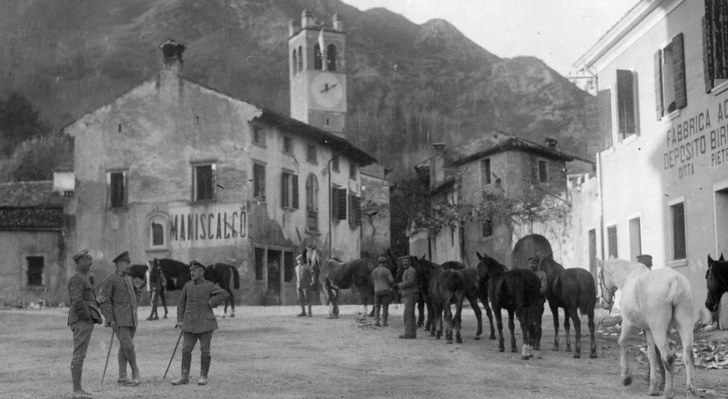

The first target was a wedge of mountainous territory, five km wide between Flitsch and Saga (now Žaga) in the north, then 25 km long, from this line to the Austrian bridgehead at Tolmein. The little town of Caporetto lies midway between Saga and Tolmein, near a gap in the Isonzo valley’s western wall of mountains. This breach, leading to the lowlands of Friuli, gave Caporetto a strategic importance quite out of proportion to its size.

6 of 7

Since Austrian military intelligence had cracked the Italian codes earlier in the year, the Central Powers were well informed about enemy dispositions in this labyrinth of ridges rising 2,000 metres, where communications were ‘as bad as could be imagined’.

7 of 7

The Germans went to great lengths to keep their presence secret. Transports arrived by night, some units wore Austrian uniforms, others were taken openly to Trentino then secretly moved eastwards. Fake orders were communicated by radio. The Austrian lines on the Carso, 40 km away, were ostentatiously weakened to deter the Italians from transferring men northwards.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- Mark Thompson, The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919, Faber and Faber Limited, London, 2008