Invasion of Poland

The beginning of World War Two

September 1939

The invasion of Poland was the first battle of World War II. This operation had the codename ‘Fall Weiss’ or Case White. The invasion was initiated by Nazi Germany and a small Slovak contingent from the newly-created Slovak puppet state. This was formed by Germany after the occupation of Czechoslovakia. Later, the Red Army invaded the eastern regions of Poland in cooperation with Germany. The Soviets fulfilled their part of the secret appendix of the Ribbentrop - Molotov pact. This pact divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, between the two powers.

1 of 7

Germany had a substantial numerical advantage over Poland. The German army had approx. 2,400 tanks, organized into six Panzer divisions. The aviation also played a major role in the campaign, with German bombers attacking Polish industrial centers.

2 of 7

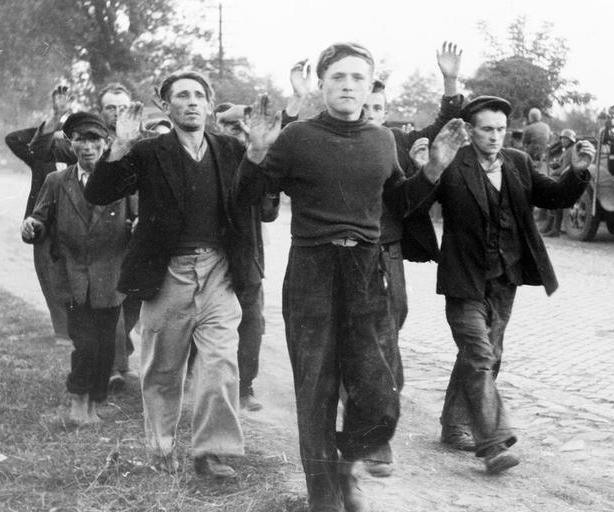

Poland had one million people in the armed forces, but less than half of these were mobilized before the beginning of the invasion. Those arriving late suffered heavy losses, as they were easy targets for the German aviation. The Polish army also had less armored vehicles than the Germans, and the ones they did have were spread out through all the infantry forces. Thus, the Poles were not able to put up an efficient fight against the enemy.

3 of 7

Lotnictwo Wojskowe, the Polish Air Force, was at a severe disadvantage compared with the German Luftwaffe, since it did not have modern fighting planes. Even so, the Polish pilots were among the best trained in the world. This was proven a year later, with Polish pilots playing an important role in the Battle of Britain.

4 of 7

The experience of the Soviet - Polish war strongly influenced the Polish army’s organization and operational doctrine. In this war, in contrast with the trench warfare of World War I, the mobility of the cavalry played a decisive role. Poland recognized the benefits of mobility, however it did not want to make massive investments in new military inventions. These were very costly and hadn’t yet had the chance to be proven efficient.

5 of 7

In total, Germany had airborne advantage both in quantity and quality. The Polish Air Force generally used the PZL P.11 and PZL P.7 fighther planes, locally-produced planes manufactured at the beginning of the 30s. These were vastly inferior to the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Messerschmitt Bf 108 planes used by German aviation.

6 of 7

The international situation and the military intimidation attempts made on Poland meant that the invasion of this country was not a surprise attack. However, Hitler hoped that the new Blitzkrieg tactics of the Wehrmacht would be a tactical shock to the Poles. Hitler had already learned that tactical surprise is an inestimable advantage in military confrontation. Throughout the whole of his revolutionary career, he always tried to use the element of surprise. It usually had great success. The Beer Hall Putsch, which he tried to pull off, surprised even his main leader, General Ludendorff.

7 of 7

Hitler’s aversion to static, attrition warfare, was a natural reaction for him. Hitler served for years in the 16th Bavarian Infantry Regiment in World War I. His tasks as battalion courier meant waiting for breaks between salvos of artillery and rushing fast in a semi-crawl from trenches to shell-holes, carrying messages. Thus, he was a courageous and conscientious soldier. Hitler probably didn’t actually kill anyone himself. He always refused promotions which would have taken him away from his colleagues. He even received two Iron Crosses, Class II and Class I.

The German army created its plan of attack based on Poland’s geography and its military capabilities. The Germans counted on conquering Warsaw with a strong attack. The invasion plan for Poland was officially called Fall Weiss or Case White.

1 of 7

The German plan for this campaign was elaborated by the head of the German General Staff of that period, General Franz Halder. He was supervised by General Walther von Brauchitsch, chief commander of the Polish campaign. All three planned assaults were in the direction of Warsaw. The main Polish army would then be surrounded and destroyed west of the Vistula.

2 of 7

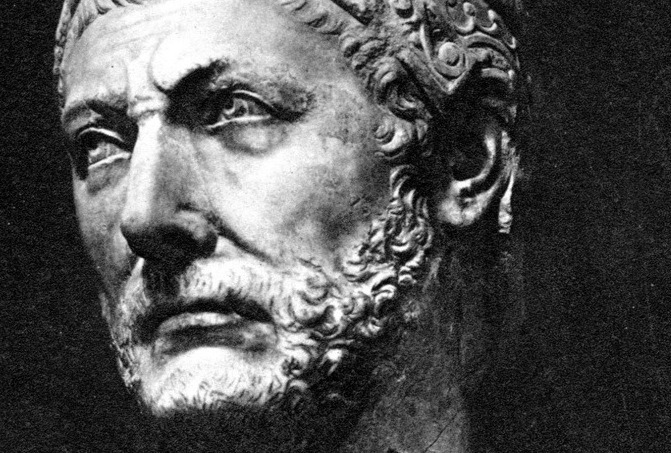

The strategy of having a weak center and two strong flanks was genius. It seems it was taken from the prewar studies of Field Marshal and Count Alfred von Schlieffen concerning the tactics used by Hannibal in the battle of Cannae. Regardless of who created the strategy, it functioned well. The strategy deftly moved the German armies between the Polish armies and allowed them to approach Warsaw simultaneously from different directions.

3 of 7

The plan stipulated the beginning of hostilities before an official declaration of war. The Germans wanted to carry out a massive encirclement and destruction of Polish forces. The infantry was supported by German tanks in order to advance rapidly and concentrate attacks on certain target points of the enemy front. The goal was to isolate and surround the enemy’s groups. Poland’s geography was well suited to such a mobile operation in good weather conditions. The country had wide plains with a very long border of 5,600 km, which was very hard to defend.

4 of 7

The British and French governments gave Poland military guarantees. Thus, Hitler was forced to leave a large percentage of the 100 divisions of his army in the west, to defend the Siegfried Line or the ‘Western Wall’. This line was made up of a series of yet unfinished fortifications, almost five kilometers wide, placed along the western border of Germany. The fear of having a war on two fronts made the Führer select forty divisions to protect his back. Still, Hitler reserved his best troops for attacking Poland, together with all his mobile and armored divisions, and almost his entire air fleet.

5 of 7

According to Case White, on each side of a relatively weak and stationary center lay two strong flanks of the Wehrmacht. They would capture Warsaw. Army Group North, under the leadership of General Fedor von Bock, would strike through the Polish Corridor. The goal of the attack was to take Danzig and meet the 3rd German Army in Western Prussia, in order to make a lightning attack on the Polish capital from the north. In the meantime, Army Group South, led by General Gerd von Rundstedt, would hit the center of the Polish forces. The group must push the front to Lwow, and also attack Warsaw from the east and north.

6 of 7

The Polish Corridor was designed by those who created the Versailles Treaty, in order to isolate Western Prussia from the rest of Germany. This had been produced as a casus belli for a long time by the Nazis, as was Danzig, a port on the Baltic Sea. This town had a majority German population.

7 of 7

Case White involved mobilizing 60 divisions to take Poland. Included in these were five Panzer divisions with 300 tanks in each and four light divisions, made up of a lesser number of tanks and a few horses. Germany also had four divisions of motorized infantry, together with 3,600 aircraft in operative aviation. The invading troops also benefitted from assistance from part of the strong Kriegsmarine, the German Navy.

- Michael Alfred Peszke, The Polish Underground Army, the Western Allies, and the Failure of Strategic Unity in World War II, McFarland & Company, Jefferson (North Carolina), 2004

- E.R. Hooton, Luftwaffe at war: Gathering storm 1933-1939, Vol.1, Chervron-Ian Allen, London, 2007

- George Sanford, Katyn and the Soviet Massacre of 1940: Truth, Justice And Memory, Routledge, London, 2005

- Steve Zaloga, Gerrard, Howard, Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2002

- Andrew Roberts, Furtuna războiului, O nouă istorie a celui de-al Doilea Război Mondial, Litera, București, 2013

- Gabriela Pantiș