World War One - the Spark

Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

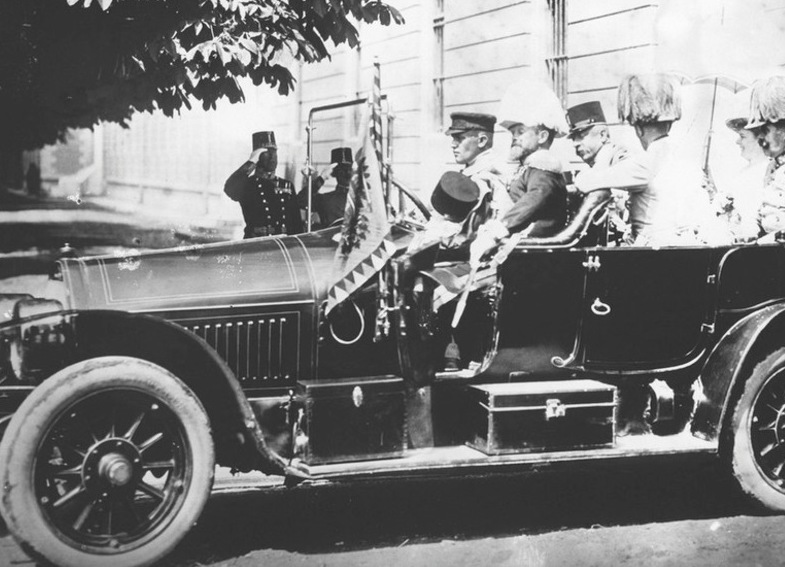

The final trigger for war would be the pent-up pressure of nationalism within the polyglot Austro-Hungarian Empire. Various nationalist groupings were making their plans. Collectively, they were highly motivated conspirators and in June 1914 they were given their chance to change the world. The culmination of months of plotting was the assassination of the Archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo on the 28th of June 1914. Franz Ferdinand was the heir presumptive of the Austro-Hungarian throne. As such, he was deemed a primary target by the Black Hand organization.

The most ... significant group would prove to be the Serbian Narodna Odbrana (National Defence) along with its rather intimidating secret terrorist wing, ‘The Black Hand’. Their intention was to liberate all Serbs from their oppressors to create a Greater Serbia, and in particular to reverse the formal annexation of Bosnia by the Austrians. To this end they had recruited a formidable membership within an interlinked nest of organizations such as ‘Young Bosnia’. The annual summer maneuvers of the Austro-Hungarian army were centered in Bosnia. The army, increasingly frustrated by what it saw as lax government in Austria and Hungary, determined that its administration of Bosnia-Herzegovina should be a model of effectiveness. Franz Ferdinand himself advocated repression and active Germanization. He was also a staunch Catholic: in Bosnia, Catholics were the minority, making up 18 percent of the population, while 42 percent were Orthodox. Many Bosnians looked wistfully to Serbia.read more

The final trigger for war would be the pent-up pressure of nationalism within the polyglot Austro-Hungarian Empire. Various nationalist groupings were making their plans. Collectively, they were highly motivated conspirators and in June 1914 they were given their chance to change the world. The culmination of months of plotting was the assassination of the Archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo on the 28th of June 1914. Franz Ferdinand was the heir presumptive of the Austro-Hungarian throne. As such, he was deemed a primary target by the Black Hand organization.

1 of 4

The most significant group would prove to be the Serbian Narodna Odbrana (National Defence) along with its rather intimidating secret terrorist wing, ‘The Black Hand’. Their intention was to liberate all Serbs from their oppressors to create a Greater Serbia, and in particular to reverse the formal annexation of Bosnia by the Austrians. To this end they had recruited a formidable membership within an interlinked nest of organizations such as ‘Young Bosnia’. The annual summer maneuvers of the Austro-Hungarian army were centered in Bosnia. In March it was announced that the Archduke Franz Ferdinand would attend the maneuvers and would visit Sarajevo.

2 of 4

The army, increasingly frustrated by what it saw as lax government in Austria and Hungary, determined that its administration of Bosnia-Herzegovina should be a model of effectiveness. Franz Ferdinand himself advocated repression and active Germanization. He was also a staunch Catholic: in Bosnia, Catholics were the minority, making up 18 percent of the population, while 42 percent were Orthodox. Many Bosnians looked wistfully to Serbia.

3 of 4

Franz Ferdinand was apprehensive about the visit, with good reason. Five assassination attempts had been made against representatives of the Habsburg administration in the previous four years. In the circumstances, and even without the benefit of hindsight, the early announcement of the visit of the heir-apparent, and the extraordinarily lax security associated with it, were inexcusable.

4 of 4

Serb subjects were implicated in Franz Ferdinand's assassination. Austria-Hungary's assumption, and indeed determination that this was the case, was shared by most of the other great powers. But the involvement of the Serb government specifically remains a moot point. Sensible diplomacy had settled crises before, notably during the powers' quarrels over position in Africa and in the disquiet raised by the Balkan Wars. Such crises, however, had touched matters of national interest only, not matters of national honor or prestige.

In the intervening period, Serbian intelligence officers covertly provided the conspirators with weapons and training, before facilitating their re-entry into Bosnia. On that fateful day the putative assassins were spread out in the waiting crowd on the streets of Sarajevo as the cars containing the Archduke and his entourage passed by. The assassins were members of a student organization called the Young Bosnians which had ties to the Serbian Black Hand organization.

1 of 2

The driving force in the Black Hand was Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijevic, known as Apis. Apis was chief of intelligence in the Serb general staff: he had used his position to help the Black Hand penetrate the army, and also to carry its activities into Austria-Hungary. Dimitrijevic’s objective, and that of his organization, was not the federal Yugoslavia favored by the Young Bosnians but a Greater Serbia, with the implication that the Serbs would dominate the Croats and Slovenes in the new state. Apis was in contact with the Russian military attaché in Belgrade, but it does not follow that Russia was privy to the assassination. Apis's stock in trade, regicide, was not congenial to the Romanovs. Apis, for his part, wanted the achievement of a Greater Serbia to be that of Serbia itself, not of Russia.

2 of 2

Major Vojislav Tankosic of the Serb army provided the four revolvers and six bombs with which the conspirators were equipped. Captain Rade Popovic commanded the Serb guards on the Bosnian frontier and had seen Princip and his associates safely into Bosnia from Serbia some four weeks before.

Battle of the Frontiers

During the first weeks of war Germany invaded Belgium in an attempt to flank the French Army. The French responded with a series of counter offensives in the Ardennes and Alsace-Lorraine, which ultimately proved disastrous for the French who suffered heavy casualties.

Battle of Mons

At Mons the British Expeditionary Force tried to hold their ground against the German onslaught into Belgium. Although the British inflicted more casualties on the Germans than they suffered themselves, they were eventually forced to retreat due to the numerical and tactical superiority of the Germans and the retreat of the French Fifth Army.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Hew Strachan, The First World War: To Arms (Volume I ), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998