Shintoist mythology

Japan, country of the Rising Sun

In Japan, not many people today declare themselves to be very spiritual. This is mainly due to the influence of modernization, education, technology and a stressful lifestyle. Even so, no one can deny the huge heritage left by different religions in Japan. Their marks on culture and mindsets can be easily observed at all levels of society. Shintoism and Buddhism, followed by Confucianism, Taoism and Christianity, affected the whole history of Japan’s unique civilization in both positive and negative ways. Actually, many different traditions intertwined together in the passing of time. Shinto-Buddhism is the result of that process, as it represents the closest thing to an official religion.

1 of 7

Japan has a declining population of 126 million people. According to the last official census made by the state between 2006 and 2008, 51% of Japanese citizens identify as atheists. Furthermore, 35% are Buddhists, 7% denied an answer, 4% are from a Shintoist sect and 2.3% are Christians. This statistic is not very relevant because it fails to analyze the widespread phenomenon of Shinto-Buddhism, the dominant religion of Japan. Shinto-Buddhism is more like a mix of beliefs and dogmas that gives a certain amount of freedom for the individual to interpret the meaning of existence.

2 of 7

Over 80% of Japanese citizens acknowledge that they often attend ceremonies at Shinto or Buddhist temples. An explanation for this apparent paradox is that Japanese people don't really believe in gods because of their highly scientific system of education. Even so, the cultural legacy of religion is so pronounced that they choose to take part in rituals as a cultural habit. Celebrations of births and weddings are mostly held in a Shinto manner, while funeral ceremonies are Buddhist. Amongst young people, Christian weddings began to be very popular.

3 of 7

Superstitions regarding things that bring you luck are widespread, especially amongst high school students who have to pass what are acknowledged by all academic standards to be very challenging exams. They go to Shinto shrines to make a wish, to be granted by a god. Other beliefs are a little bit scarier. For example, it is said that you shouldn't use sharp objects when it is dark because metal objects have mystical evil powers called reiryoku. Some think that you can curse someone if you go to a temple with a straw doll and a needle after midnight.

4 of 7

Historical cities like Kyoto organize tremendous religious festivals almost on a daily basis. Some are original Japanese traditions, and some are modified versions of ceremonies inspired from ancient China and Korea. The celebrations revolve around big crowds dressed in demons and other mythical creatures that march on the streets. Reconstruction of historical, heroic or legendary battles are the most widespread, followed by food festivals, cherry blossom contemplation, fireworks called hanami and firefly admiration.

5 of 7

Buddhism and Shinto have a different background, but are perfectly compatible with each other. The first offers a guide on how to walk between good and evil, while the latter works as an bond with the ancestors. Starting from 2012, the government decided to implement the teaching of Shinto myths beginning with elementary school. Ethics and basic civic education are taught from a very early age.

6 of 7

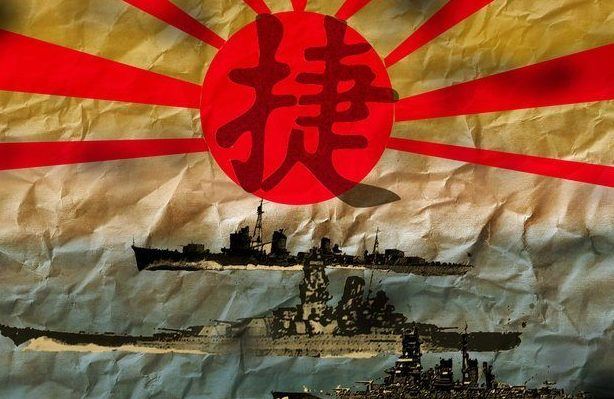

Unfortunately, Shinto also has a dark past. The imperial authorities from the interwar period and the Second World War used Shinto legends as political propaganda. At an official level, myths were held up as scientific truths, beyond any doubts and criticism. Turning a religion into an ideology had the purpose of justifying the act of conquering other neighbours which didn’t have a divine origin or special destiny ordained by the gods. After World War II, Tokyo apologised for all its crimes and started a pacifistic program of reeducation.

7 of 7

Incidents related to the imperialistic past are still present. For example, in 1999, prime minister Yoshiro Mori declared that Japan is the ‘country of the gods’, a statement that infuriated China and other states from the Pacific region. Moreover, the current prime minister, Shinzo Abe, visited the Shinto shrines dedicated to the Japanese soldiers who died in the Second World War. He refused to apologise, maintaining that honoring heroes is the natural right of every country and that enough time has passed since the last big war.

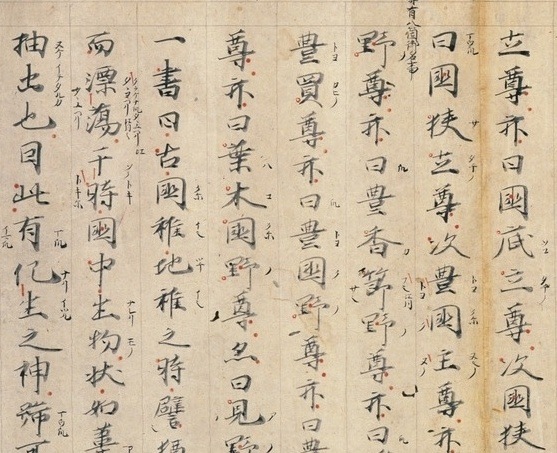

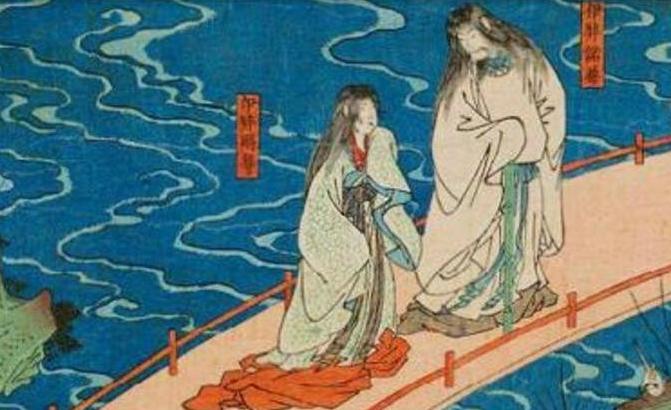

Shinto’s exact date of creation is unknown. The original tales that created the pantheon of gods and other supernatural beings come from the immemorial times of the paleolithic age. Because a written language didn't exist at that time, legends were transmitted orally. This is why so many different versions of particular stories emerged in a luxurious collection of old wisdom and fantasy, comparable with Ancient Greece. The first books recording Japanese folklore were Kojiki and Nihon shoki. They were ordered by the empress Genmei and interpreted by scholars in a way that benefited the state.

1 of 6

Shinto was the only truly original spiritual creation of the archipelago. It’s an animistic religion closely connected with nature. In fact, Shinto gods and mythical beings are mostly personifications of phenomena that can be found in nature. It also explains the divine origins of the Japanese people, and their heroic qualities. On the other hand, different forms of Buddhism were borrowed from China and Korea. The main stake is not explaining the supernatural world, but obtaining redemption into Nirvana either by praying or by living a good life, according to the dogma.

2 of 6

As a primitive system of beliefs, Shinto does not focus on an ethical code and it doesn't say much about how we should behave or what should we do with our lives. The main idea is to keep in balance all the divine forces that can become good or evil. Spirits start to be malevolent only when harmony is broken. In contrast to other systems of belief, there is no innate good or evil. Society and unfortunate events corrupt the human heart.

3 of 6

Having in mind that Kojiki and Nihon shoki represented the official approach of the state in religious matters, it’s logical to deduce that many different versions still endured in the countryside. Most of the political elite converted to Buddhism imported from China via Korea, while the common folk remained loyal to their Shinto gods.

4 of 6

Archeologists estimate that the first clear Shinto system of beliefs commenced somewhere between 300 BC and 300 AD. The most common form of ritual was a communication with the gods called kami, using shamanistic intermediaries. Respecting your ancestors was also of primordial significance since their purpose was to protect the living.

5 of 6

It’s not important whether the Japanese are atheists or believers. Shinto played the role of creating social values in the same way protestantism encouraged the development of capitalism in northern Europe. The main characteristics are: purification using rituals, loyalty to the family, respect for nature and all its beings, fertility ceremonies and the importance of the society as a whole instead of the individual.

6 of 6

While Kojiki was written by the scholar Yasumaro, Nihon Shoki was composed by several authors. The second holy book was a response by the other noble families who felt displaced. Nihon shoki corrected the perception that all the great heroes came only from the Yamato family. It also described the relations between deities and heroes in a far more detailed manner.

- Paul Varley - Cultura japoneză, Humanitas, București, 2017

- Inazo Nitobe- Bushido, the soul of Japan, Gobancho, Tokyo, 1908

- Yuri Yasuda- A treasury of Japanese Folktales, Tuttle, Tokyo, 2014

- Curtis Andressen - A short history of Japan from Samurai to Sony, Allen and Unwin, Canberra, 2002

- C. Scott Littleton - Yamato-takeru: An Arthurian Hero in Japanese Tradition, Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 54, No. 2, p. 259-274, 1995

- Okakura Kakuzo - The book of Tea, Penguin Classics, New York, 1906

- Sven Saaler, J. Victor Koschmann - Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History. Colonialism, Regionalism and Borders, Routledge, New York, 2007

- Jason Ananda Josephson - The invention of Religion in Japan, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2012

- William Elliot Griffis - The Religions of Japan: From the Dawn of History to the Era of Meiji, HardPress Publishing, 2012

- George Tanabe - Religions of Japan in Practice, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1999

- Yei Theodora Ozaki - Japanese Fairy Tales, Tuttle, 2007

- Richard Gordon Smith - Ancient Tales and Folklore of Japan, Sagwan Press, London, 2015

- Sidney L. Gulick - Evolution of the Japanese, Social and Psychic, Echo Library, Japan, 2007

- Michael Ashkenazi - Handbook of Japanese Mythology, ABC -CLIO publishing, California, 2003