Serbian Campaign

Central Powers invasion of Serbia

28 July 1914 - 3 November 1918

The Serbian Campaign in the Great War started when the Austro-Hungarian Empire attacked the Kingdom of Serbia. The invasion became a disaster for the Austro-Hungarians when the Serbian army turned out to be a tougher opponent than anticipated. As such, the Serbians managed to succesfully defend their homeland in 1914. In the following year however the Austrians, with German help, managed to defeat the Serbians who retreated their armies to Greece, through Albania, where they could reorganize under the protection of the other Entente combatants. Serbia was under Central Powers occupation until the end of the war in 1918.

1 of 5

Serbia's geographical position made it the strategic keystone of the Balkan peninsula. The terrain was wild and mountainous but two historic Balkan trade routes passed through it along the Morava-Maritza Trench, known as the 'Diagonal Furrow' (the line selected for the Berlin-Baghdad railway), and the Morava-Vardar Trench, connecting Central Europe with the Aegean. Serbia's northern frontier was shielded by natural barriers: the rivers Drina and Danube. A third barrier, the river Sava, was lined with near-impassable marshes. Road communication throughout the country was extremely poor.

2 of 5

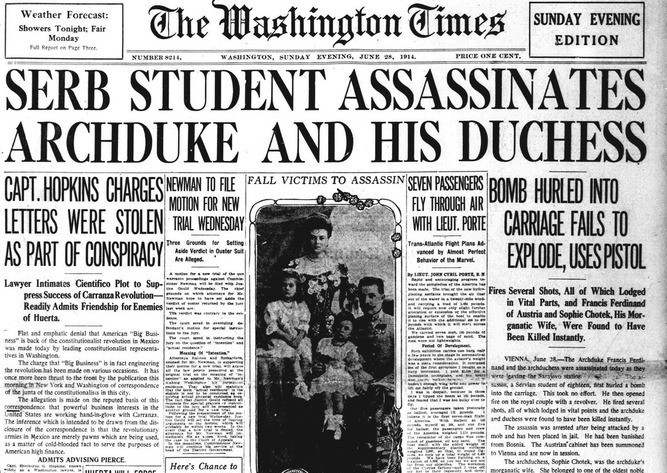

Austria's principal emotional, if not rational, war aim was the punishment of Serbia, which had precipitated the July crisis by its involvement in the Sarajevo assassinations. Sense would have argued that Austria should deploy its whole strength forward of the Carpathians to engage the Russians. Outrage, combined with decades of provocation, demanded the defeat of the Belgrade government and the upstart Karadjordjevic dynasty.

3 of 5

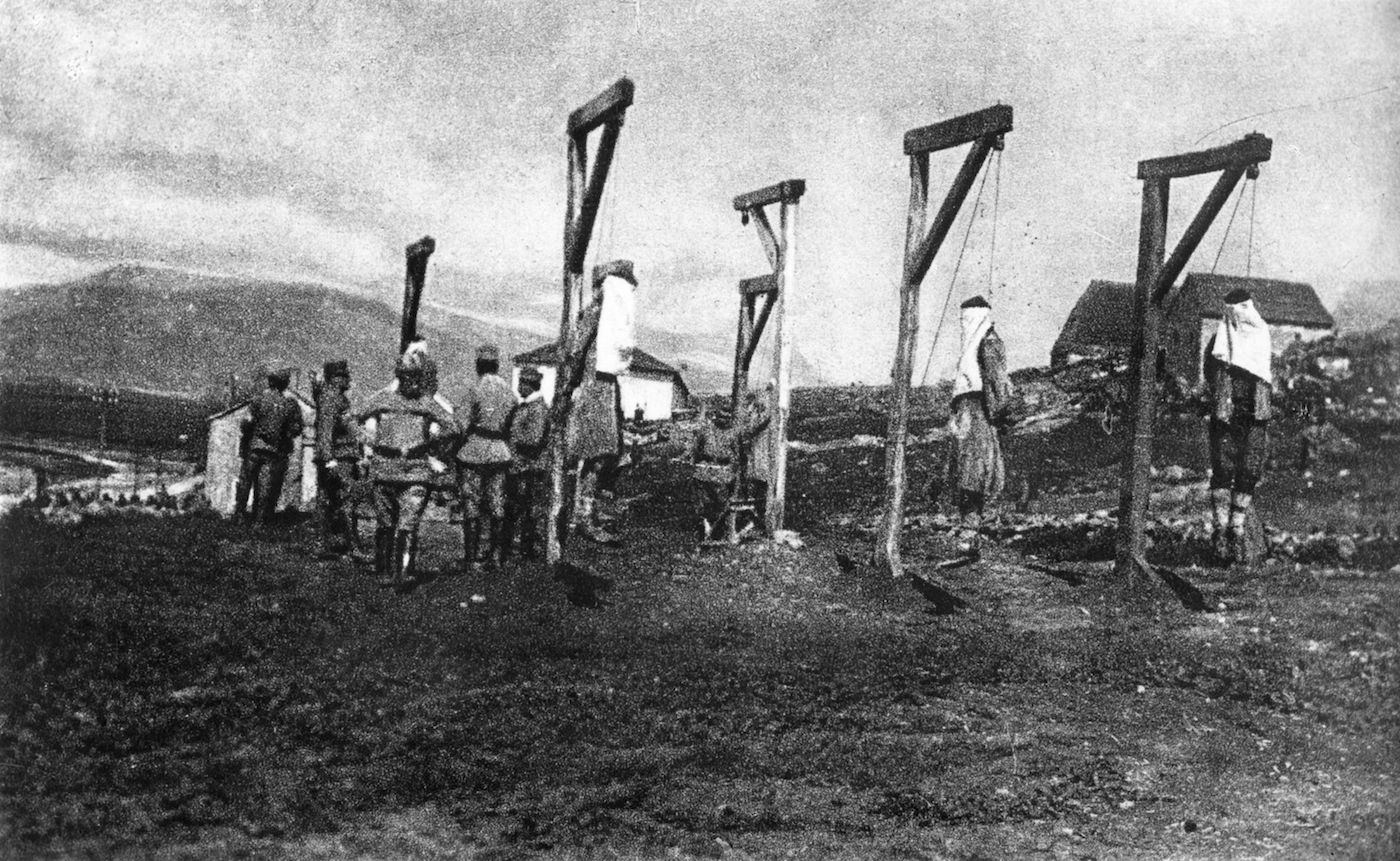

The Serbian officer corps' participation in the murder and mutilation of the Obrenovic King and Queen in 1903, and the widely reported practice of mutilation of corpses during the Balkan Wars had led the Austrian army to imagine that a campaign in the Balkans would present little more difficulty than the British or French commonly encountered in their colonial campaigns in Africa or Asia. The Austrians expected a walkover. In fact the Serbs, despite their cruelty during the Balkan Wars, were not at all militarily backwards in tactics.

4 of 5

The political pressure for an early attack on Serbia was considerable. Domestically, victory would quash irredentism; diplomatically, it would provide the foundations for a Balkan alliance. Strategically, pure defense against Serbia was not recommended, since it would involve inferior forces stretched along a frontier totalling 600 kilometres, with lateral communications so poor that rapid concentration would be impossible.

5 of 5

The Austro-Hungarian campaign against Serbia in 1914 failed to meet any of the required political objectives of 1914. Vienna could not 'halt at Belgrade' as the Kaiser requested because it had no plan for such an operation; nor could the army deliver the quick victory the diplomats wanted in order to shore up the empire's position in the Balkans.

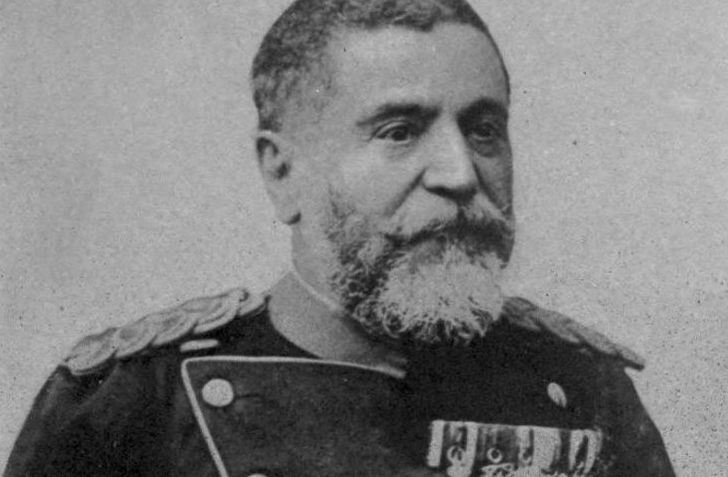

The approximately 200,000-strong Serbian Army was commanded by the elderly figure of Field Marshal Radomir Putnik. He would prove a formidable directing intelligence to Serbian military operations. The Serbian Army had recent experience in the Balkan Wars, but it was woefully ill-equipped for a full scale conflict with a major power.

1 of 6

Putnik had to endure the embarrassment of being promptly imprisoned by the Austrians in Budapest, where he had been undergoing an untimely medical treatment when the war started. Strangely, he was then released, presumably because the Austrians thought he would hardly be fit to exercise a competent wartime command. However, his offer to resign on the grounds of ill health having been rejected by King Peter I of Serbia, Putnik went on to oversee the strategic direction of the Serbian Army, while his subordinates did all the work in the field.

2 of 6

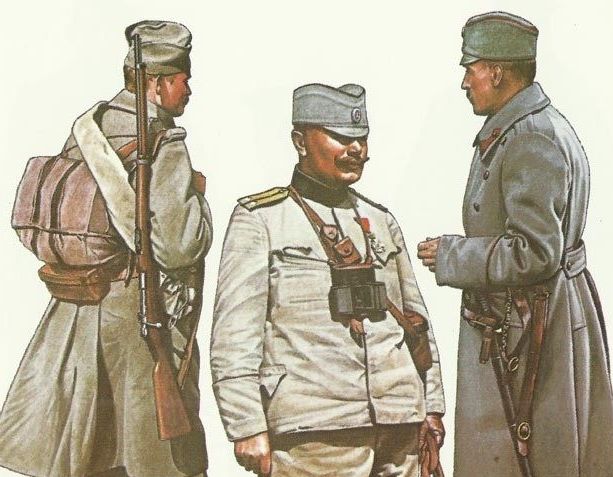

The small Serbian First, Second and Third Armies faced the 270,000 men amassed in the Austrian Fifth and Sixth Armies with little immediate tactical ambitions other than to endure till their Russian allies had triumphed. The strength of the Serbian army lay in the endurance and courage of its officers and soldiers, who displayed amazing powers of survival in their campaigns.

3 of 6

The Serbian military system demanded universal service for all able-bodied males from the age of 18 to 45. The system of conscription mobilized, even if by informal means, a higher proportion of the male population than in any other European country. The army conspicuously lacked motorized transport, due in part to the appalling standard of Serbian roads, generally impassable to motors after rain. The army's transportation relied on animals. Baggage trains, bridging equipment and artillery were all drawn by oxen.

4 of 6

The Balkan wars had also weakened the Serb army. The newly acquired territories had not been fully assimilated for military purposes, and parts were in near revolt. Total losses may have risen as high as 91,000. More serious for a country of economic backwardness was the loss of equipment and the expenditure of ammunition. On 31 May 1914 the minister of war, having embarked on a ten-year program to rebuild the army, declared that Serbia was not yet fit to fight.

5 of 6

The rifles in use were of a variety of types (ironically, the best and most widely used, Mausers, had been supplied by Germany), and there were only enough modern patterns for the peacetime complement of 180,000. In some units up to 30 percent of infantrymen had no rifles at all. There was less than one machine gun for each infantry battalion. The Serbs had acquired 272 75 mm field guns from the French, and had better field howitzers than the Austrians. But after they had given 100 guns to Montenegro, their total complement of field guns was 528, of which only 381 were quickfirers. The recent fighting had depleted shell stocks.

6 of 6

The Serbs' reliance on the Entente powers for equipment created a dependence that robbed them of strategic freedom, and a vulnerability which their land-locked isolation did nothing to mitigate. The Russians sent 150,000 rifles, the French sent artillery; in exchange, both powers demanded that the Serbs attack.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Hew Strachan, The First World War: To Arms (Volume I ), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998