Romania enters World War I

The Central Powers defeat Romania

27 August - 6 December 1916

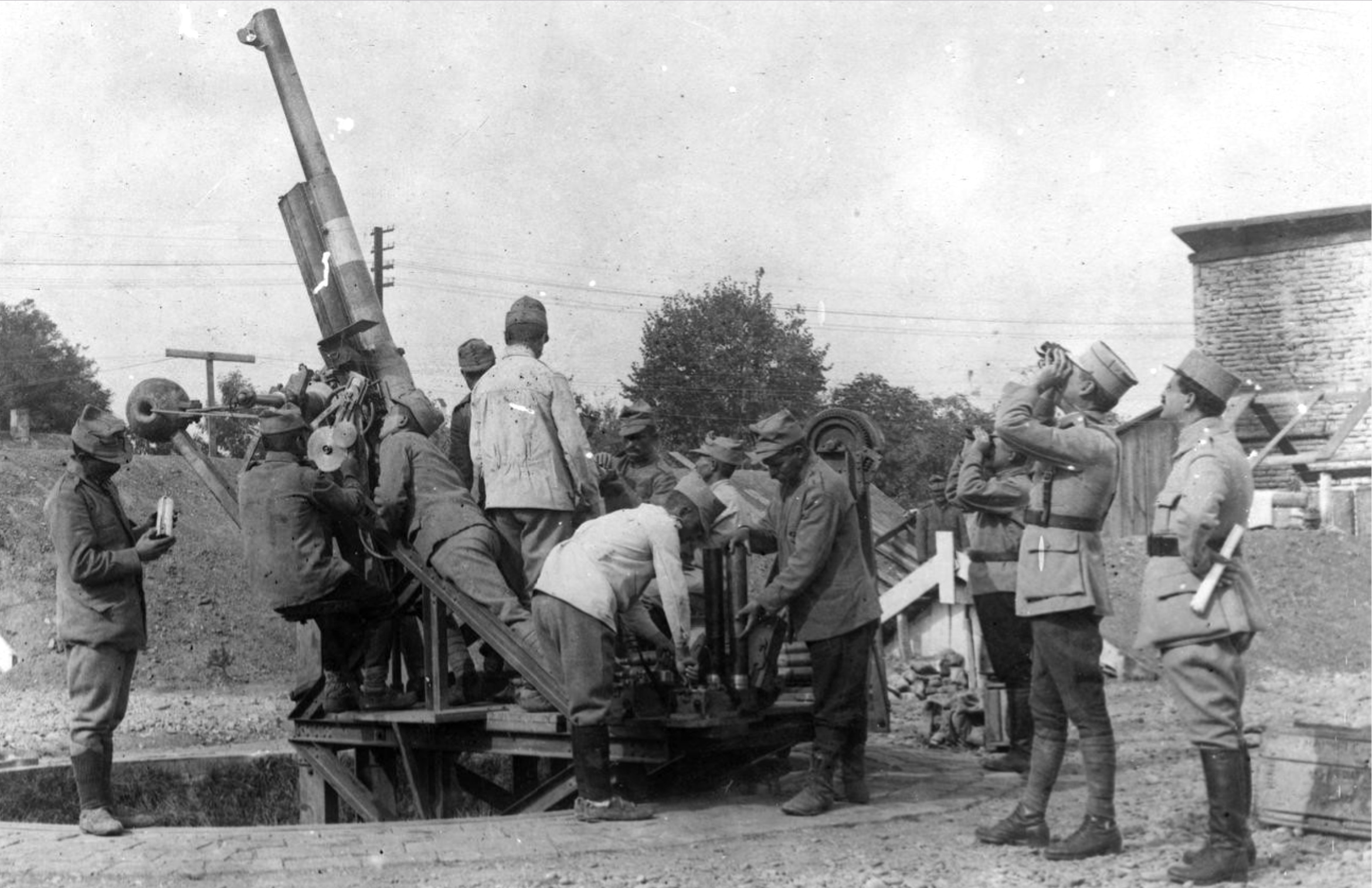

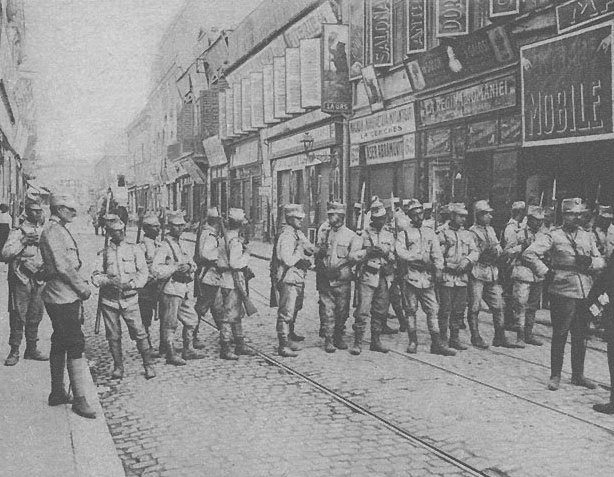

After the Brusilov Offensive, Romania, which had been long courted by the Entente, but had until then chosen to stay neutral, entered the war. Romania’s primary goal was acquiring Transylvania from Austro-Hungary. Thus it was that the first military action of the Romanian army was the invasion of Transylvania through the Carpathian passes. The Central Powers response came swiftly, pushing the Romanians out of Transylvania and invading the country from the west and south. The capital, Bucharest, was conquered. All told, the Romanian interlude was a disaster for the Entente and a morale-boosting victory with very tangible rewards for the Central Powers.

1 of 6

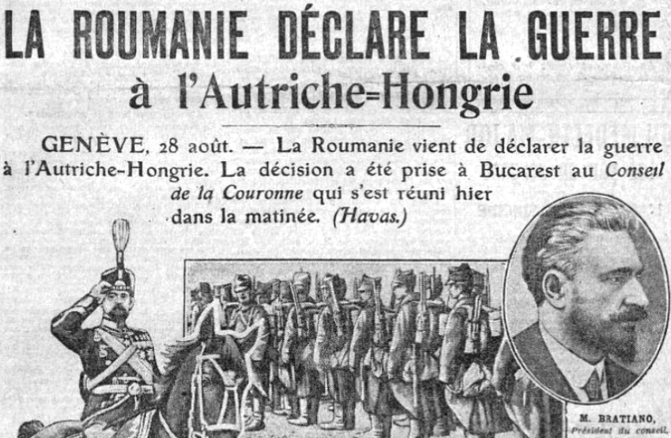

Romania declared war on Austria-Hungary and promptly invaded Transylvania via the passes through the Carpathians and Transylvanian Alps. It would prove a momentous decision, but not quite in the way that the Romanians had hoped.

2 of 6

It soon became clear that the Romanian armies would be incapable of prolonged resistance. Even the wide waters of the Danube could not stop the Germans, while they eventually burst through the deep passes of the Transylvanian Alps. By then the hapless Romanians were in a state of collapse and there was nothing their new allies could do to help them.

3 of 6

The Germans entered Bucharest in triumph and the Romanians were forced to acknowledge defeat. The Ploiesti oil fields, thirty-five miles north of the capital, were also overrun, and they would prove an invaluable prize to the oil-starved Central Powers.

4 of 6

Over the next year the Germans would raid Romania for much-needed supplies of oil, grain, farm animals and wood, succeeding to an extent in defraying the inconveniences of the British blockade in the North Sea.

5 of 6

Italy’s entry into the war was from the start a mixed blessing, but in the spring of 1915 it looked quite promising, and at the end of the year, with Serbia occupied and the debris of the Serbian Army stranded in the Adriatic, the Entente looked around for another partner. Calculating everything by the gross, they decided that since Romania had a total military of nearly three quarters of a million men, and since Austria-Hungary was reeling on the verge of collapse, the entry into the war of hundreds of thousands of Romanians would be the straw that broke the camel’s back. This did not prove to be the case.

6 of 6

So long as the Central Powers appeared invincible, Romania could not risk intervening against them. Her strategic situation was peculiarly vulnerable. But with the great run of Russian victories, her confidence rose. Moreover, by August 1916, the western Powers were prepared to guarantee much more territory than before: the French, in particular, with an eye to the post-war situation, wanted to establish a greater Romania as a bulwark against Russia.

The Entente had long been wooing Romania, which had an interest in joining the war. This interest was Transylvania, Hungarian-ruled, but mostly Romanian-populated. However, Romania could only hope to get it if the Entente won, and up to mid-1916 that did not look very likely. Besides, should a Central Powers victory put Transylvania out of reach, Russian Bessarabia (now the Republic of Moldova), also mostly Romanian-populated, could be a consolation prize. Strategic vulnerability also dictated caution. Romania had very long frontiers relative to its area, and its neighbours from the West and South were already in the Central Powers camp.

1 of 5

Bulgaria had joined the Central Powers in September 1915, had a territorial claim against Romanian Dobrudja and could well pursue it militarily if Romania joined the Entente. Bucharest would then be particularly endangered, as it was only 30 miles (48 km) from the Bulgarian border.

2 of 5

Romania’s chief national interest was the addition to its territory of Transylvania, where three million ethnic Romanians lived under Austro-Hungarian rule. As Brusilov's advance pushed westward, widening the common border of military contact between Russia and Romania and apparently promising not only Russian support but Austrian collapse, the Romanian government's indecision diminished. Prudence probably dictated staying neutral, but General Brusilov's successes created a chance for Romania to seize Transylvania while Austria-Hungary was fully stretched. Thus Romania declared war.

3 of 5

Good sense should have told the Romanians that their strategic situation, pinioned between a hostile Bulgaria to the south and a hostile Austria-Hungary to their west and north, was too precarious to be offset by the possible support of a Russian army which had only belatedly returned to the offensive.

4 of 5

The Romanians had been following the war with interest, trying to figure out how they could benefit from it. As the example of Serbia had shown, there was no profit in tangling with the Austro-German-Bulgarian triad unless you had serious support. The Romanians were less than enthusiastic about their nearest potential supporter, Russia. For Romania to be persuaded to enter the war, the ‘bribe’ would have to be substantial.

5 of 5

Romania would be given Transylvania. In no case would the inhabitants of these areas be allowed to decide their fate; they were simply handed over. In order to bring Romania into the war, the Entente not only appealed to that nation’s greed, they then sweetened the deal by making promises of military support, which they ultimately did not keep and probably had no intention of keeping.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- John Mosier, The Myth of the Great War: A New Military History of World War I, Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney, 2001

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Norman Stone, The Eastern Front 1914-1917, Penguin Books, London, 1998