Nara

The Japanese chronicles, grandiose temples and the rise of the Fujiwara clan

710 - 794

Nara jidai is a relative short period of time in the history of Japan, placed between Asuka jidai and Heian jidai. The name of the era is given by its capital, called at that time Heijokyo, later renamed Nara. The capital was built after the foundation of Chang-an, the great capital of the Chinese Tang dynasty. It was a period of slow transition from a centralized state to a more decentralized one. Culture flourished under the inspiration of the Tang empire and the Korean kingdoms Silla and Balhae. At the same time, Japan started to consolidate its own national identity and managed to build temples that are now under the protection of the UNESCO patrimony.

1 of 7

The Japanese emperors continued the reforms of centralization begun in Asuka jidai. This eventually led to the general discontent of the nobles. A rebellion against the emperor was started by Fujiwara Hirotsugu. He was supported by important Shinto clans from the southern part of Kyushu. They contested the Yamato dominance and the imposition of Buddhism. With a strong army of 20,000 soldiers, emperor Shomu won the war and killed Hirotsugu. Ironically, even though the rebellion was defeated, the Fujiwara clan continued to have the most important political role in the imperial court.

2 of 7

In order to appease the unrest, emperor Shomu canceled the clear separation of religion from politics. The Kokubunji system was proclaimed. The holy temple network of Todaiji was built, and functioned as a national temple. Furthermore, in each province a Buddhist monastery was constructed. The autonomy given to the Buddhist monks turned out to be unwise. Because they offered services to the poor, Buddhist monks became very popular among common folk. In time, they were able to train, develop martial arts that became a legend in their own right, and even put together small armies that could offer them political power.

3 of 7

Common people suffered because of the ambitious investments of their political elite. The vast majority of the population was vulnerable to crop failure, starvation, epidemics and natural disasters. The national collective farming system was breaking down. In order to keep up with all the bureaucratic data, the central government hired 10,000 functionaries. Under those conditions, the emperor gave back the peasants’ rights of inheritance over their land. The plan backfired when local warlords and clan leaders started to act more autonomously, bypassing the imperial authority.

4 of 7

One of the most famous Buddhist monks from Nara jidai was Dokyo. Using his influence over Empress Koken, he managed to be named heir to the imperial throne. Only through the intervention of the Fujiwara clan was his entronment avoided, and Dokyo was exiled. This incident shows how important the monopoly of Buddhism was. The failure of the coup had another consequence. From now on, only men could be named emperors and directly rule the country. On the other hand, compared to the rest of the world, the ancient Japanese noble women had many rights: to be educated, to own private property, and even the right to fight in wars.

5 of 7

Because of repeated nationwide epidemics and starvation, Japan lost around 30% of its population during the century of Nara jidai. This disaster was created by the occurrence of viruses which up until then had been unknown, and by the lack of farming land. Instead of redirecting funds in order to tackle this grave situation, the political elite prefered to invest in the building of temples and ambitious infrastructure projects. Their isolation from the real local problems did not prevent them from suffering. For example, a dynastic crisis started when all four of Fujiwara Fuhito’s heirs died in a smallpox epidemic.

6 of 7

The entire burden of taxes was carried by the peasants, who were already suffering from poverty. Nobles and Buddhist monks were exempt from taxes. The discontent of the majority of the population was suppressed by a national army. Most of the soldiers were loyal to the emperor as long as they were paid. These serious problems were interpreted by emperor Shomu as a divine sign that he must push forward with the promotion of Buddhism. The costs of the project exhausted the national treasury and the soldiers started to be more loyal to local lords who could pay them better.

7 of 7

The Otomo, Tachibana and Fujiwara clans fought by the means of complex political scheming and assassinations in order to gain control of the central government and the power to manipulate the emperor. At the end of Nara jidai, the Fujiwara clan won the competition and started to rule in the name of the emperors as regents. Leaving aside the political, economic and social environment of the era, Nara jidai remained in the history of Japan as a symbol for cultural development. This is when the great ancient chronicles and collections of poems like Kojiki, Nihon shoki, Kaifuso and Manyoshu were written.

There is a clear difference between Asuka and Nara. Nara jidai was an era defined by two opposing forces: centralization coming from the imperial family versus the decentralization sought by the aristocratic clans. The first part of the period was dominated by the emperor and his close advisors, but the end of the era marked the rise of the Fujiwara family as the real rulers of Japan. From an ideological perspective, Buddhism and Confucianism were favored by the elites, while most of the peasants preserved their Shinto traditional faith. However, comparatively, Buddhism won the most ground in a short period of time.

1 of 5

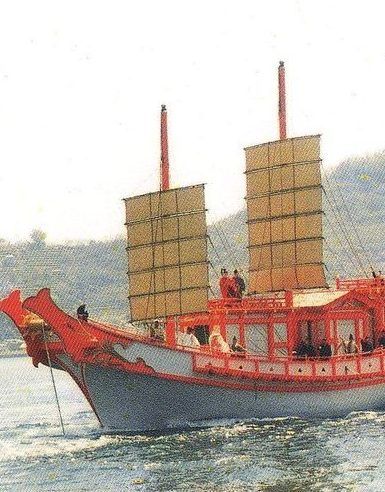

At the end of Asuka jidai, Japan was defeated by a Silla-Tang alliance at the battle of Baekgang in 663. A few years later, Silla turned against its former ally, and this motivated the Tang emperor to try to reconcile with Japan. Historians discovered a Japanese report sent to the emperor in 671. It seems that a huge Tang diplomatic mission reached the shores of Japan. The ships carried six hundred Chinese and fourteen hundred Japanese prisoners of war. The mission was a failure because emperor Tenmu was busy fighting a civil war and consolidating his internal powerbase.

2 of 5

According to the Japanese historian Naoki Kojiro, the base for the political reforms in the Nara jidai was created by one of the last rulers of the previous era, Emperor Tenmu. His reign wasn’t based only on military or economic force, but on the ideological legitimacy given by state religion. A new generation of nobility was created, a ruling class promoted on the basis of their services for the emperor and for the nation. For local nobles, access to the imperial court meant access to real political power. In a comparative sense, Tenmu played the role of Louis the XIV of France when he forced the aristocracy to move to Versailles.

3 of 5

Nara jidai was different from what had happened in the past because the Japanese imperial house preferred to focus on social and political reforms instead of developing their military. All the foreign contacts they had in this period of time with the Korean kingdoms of Silla and Balhae, or with the Chinese Tang dynasty, were peaceful. The Japanese emissaries were particularly interested in gathering Buddhist and Confucian texts. The idea of any military expedition in Korea was abandoned as it had become clear that Silla and Tang had their own problems and didn’t intend to invade Japan.

4 of 5

Tenmu was the first strong Japanese emperor who claimed to be the heir of the sun goddess Amaterasu, making him the representative of one of the most important deities of the Shinto pantheon. All the edicts started with a phrase that stated that the emperor's laws are the expression of a god. The emperor had the absolute power to appoint all the important priests, to organize the most sacred rituals and to rank the most relevant shrines worthy of worship. Before his reign, all those decisions were negotiated with other clan leaders. This type of both secular and sacred power held by the emperor became a long-standing tradition.

5 of 5

Just two years before the Nara capital was finished, copper mining was discovered in Japan. This made historians speculate that the administrative reforms of the Nara jidai were more closely linked to wider technological developments than to religious or political causes.

- Paul Varley - Cultura japoneză, Humanitas, București, 2017

- Curtis Andressen - A short history of Japan from Samurai to Sony, Allen and Unwin, Canberra, 2002

- W. G. Beasley - The Japanese Experience. A short history of Japan, The Orion publishing group, London, 1999

- Kenneth Henshall - A history of Japan from Stone Age to Superpower, Palgrave Macmillan, New Zealand, 2012

- Donald Denoon, Mark Hudson, Gavan McCormack, Tessa Morris-Suzuki - Multicultural Japan: Palaeolithic to Postmodern, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2001

- W. Scott Morton, J. Kenneth Olenik, Charlton Lewis - Japan Its History and Culture: 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill Publishing, New York, 2005

- Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Anne Walthall, James Palais - East Asia. A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Houghton Mifflin Publishing, New York, 2009

- George Sansom - A History of Japan to 1334, Charles E. Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo, 1958

- Delmer M. Brown - The Cambridge History of Japan Volume 1, Ancient Japan, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993

- Karl F. Friday - Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850, Westview Press, Colorado, 2012

- R.H.P. Mason & J.G. Caiger - A History of Japan Revised Edition, Tuttle Publishing, Singapore, 1997

- P. C. Swann- The Art of Japan From the Jomon to the Tokugawa Period, Greystone Press, New York, 1966

- Noritake Tsuda - A history of Japanese Art. From Prehistory to the Taisho Period, Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo, 2009

- Penelope Mason - History of Japanese Art. Second Edition, Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2005

- Donald Keene, Seeds in the Heart. Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century, Henry Holt and Company Publishing, New York, 1993

- John Dougill - Japan’s World Heritage Sites. Unique Culture, Unique Nature, Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo, 2014

- William Wayne Farris - Japan to 1600: A Social and Economic History, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2009

- William Wayne Farris - Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1998

- Herman Ooms - Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan. The Tenmu Dynasty: 650-800, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2009

- Bender Ross - Performative Loci of the Imperial Edicts in Nara Japan: 749-70, Oral Tradition, volume 24, number 1, pp. 249-268, 2009

- Bender Ross - The Hachiman Cult and the Dokyo Incident, Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 34, number 2, pp. 125-153, 1979

- Bender Ross - Changing the Calendar. Royal Political Theology and the Suppression of the Tachibana Naramaro Conspiracy of 757, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 37, number 2, pp. 223–245, 2010

- Jean-Pascal Bassino and Masanori Takashima - Paying the Price for Spiritual Enlightenment. Tax Pressure and Living Standards in Kofun and Asuka-Nara Japan (ca. 300-794 AD), Economic History Society Conference, University of Warwick, pp. 1-26, 2013