Jomon, Late Paleolithic and Neolithic

Anthropology, Archaeology and the cultural and genetic origins of the Japanese

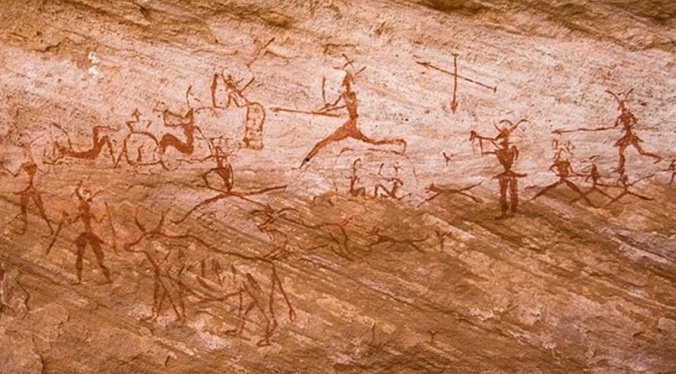

The geographical position of Japan significantly shaped its history, beginning in prehistoric times. When the climate was cold, the Japanese archipelago was united to the mainland of Asia by bridges of ice. People from different places migrated to Japanese soil. When global warming began, the ice melted and the inhabitants started to live on a chain of islands. Nature dictated the isolation of very diverse tribes and populations, each with its own traditions, and created the conditions for the rise of a new and unique culture.

1 of 5

The origins of the first people in Japan are unknown even to this day, with archaeologists and historians debating the problem of their ethnic character. Some evidence suggests they came from China via Korea, some that they came from Indochina and the Indonesian archipelago, while other findings incline the balance for Siberia. It is possible that in the Ice Age they came from all those regions, starting to become a more homogeneous culture only after they were forced by natural conditions to live in isolation from the rest of the Asian continent.

2 of 5

The Japanese archipelago contains about 7,000 islands but, considering the actual living space and population, only four are really important: Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku and Hokkaido. Most of the population settled in the southern parts like Kyushu and Shikoku, or in the north-eastern parts of Honshu, the main island. The living conditions were favorable because of the warm weather and plentiful rain coming from the Ryukyu islands which have a subtropical climate. This stimulated a very diversified ecosystem of 90,000 species of animals that now live in Japan.

3 of 5

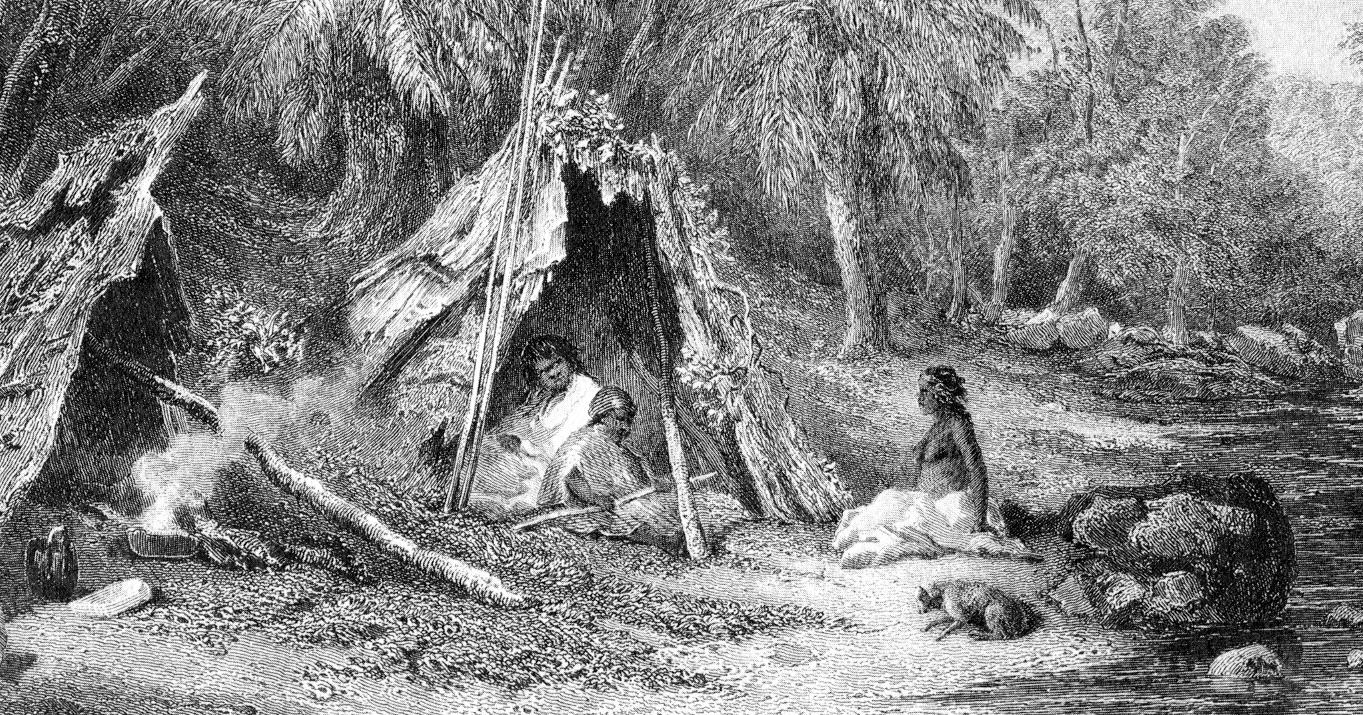

Hokkaido was called Ezo until 1869, after the name of the people that lived there, known now as the Ainu people. Because of the very cold Siberian climate, the island was largely uninhabited until the sixteenth century. The Ainu lived in northern Honshu and Hokkaido, with different traditions from the rest of the Japanese, since they came from Siberia. They are the last survivors of the Neolithic period in Japan, the rest of the populations being assimilated by later migrators. Today there are still around 200,000 Japanese citizens with Ainu ancestry.

4 of 5

Japan has a surface area of approximately 377,000 square kilometers. The terrain is 70% forested mountains, with a biodiversity of at least nine different types of forests that range from temperate coniferous forests to humid subtropical ones. There are approximately 500 mountains that have an altitude of 2,000 meters or higher. Of the multitude of national parks, four are protected by UNESCO. The ecosystem influenced the first cultures in Japan’s prehistoric time, making them hunter-gatherers that were very skilled in fishing and woodworking.

5 of 5

The Japanese archipelago rose from the sea 14,000-15,000 million years ago from the subduction with Eurasia. It is situated at the intersection of the tectonic plate of the Philippines, or in a broader sense, of the tectonic plate of the Pacific, with Eurasia, North America and Indo-Australia in south. The consequence is that from the dawn of history, the people living in the area had to deal with some of the worst earthquakes, tsunamis and active volcanoes in the world. Anthropologists think that natural disasters created an archaic special relationship with death in the Japanese culture.

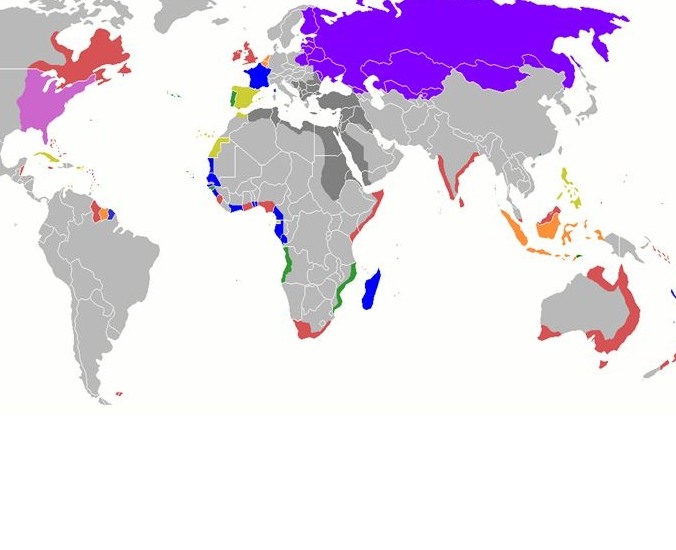

The ancient cultures from Asia were superior to, or at least the equals of, the cultures from Europe. Ian Morris is a British historian and a reputed professor at the University of Stanford. In his book: ‘Why the West Rules for Now. The patterns of history and what they reveal about the future’, he tries to explain why Asia was the center of humanity until the late Middle Ages and why Europe started rising in modern times. The demonstration is called the Morris Theorem.

1 of 5

From an epistemological point of view, Morris bases his theory on three interdisciplinary pillars. The first is biology, understood by him to include human nature and the immediate natural resources that are available for a particular society. The second is sociology, meaning a comparative analysis using social science instruments. The third is geography, especially at a physical, economic and human level. These three pillars can’t be separated if we want to understand history.

2 of 5

The lack of a vast natural diversity favored the foundation of self-satisfied kingdoms and empires in Asia, while Europe's very miscellaneous geography stimulated competition and prevented the formation of conservative empires. Large armies that will conquer all Europe were not possible because of the lack of general population density and the limitation dictated by the existence of small and middle realms that were adapted to the local natural conditions. Unlike the steppes of Asia, vast cavalry charges were useless when they had to pass a great number of rivers and forested mountains.

3 of 5

Morris justifies how his theory works: ‘Biology explains to us why the society evolves, sociology tells us how they do it, while geography explains why the West, and no other region of the world, has dominated the globe in the last two hundred years. Biology and sociology offer us universal laws, whereas geography explains the differences.’ The historian thinks that we should focus not only on the modern past, but seek answers in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Age. The Morris Theorem states that major social progress and technological discoveries do not appear from hard work and dedication to local customs and habits, but tend to rise from despair. Natural disasters, superpopulation, epidemics, famine and wars stimulate people to innovate. He says that people who are lazy, greedy or scared are the greatest revolutionaries. Chaos stimulates creativity for opportunists and danger motivates them to fight for survival.

4 of 5

Crises bring forth alternative solutions. Only the most feasible ones endure. The problem is, in Ian Morris’s opinion, that the solutions create new artificial needs that are the root to the next crisis. Because people from Asia, including Japan, had a difficult time fighting harsh conditions, they created advanced cultures and civilizations.

5 of 5

Constant fighting without a clear winner in Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire encouraged reforms and modernization. In the time that China, Korea and Japan decided to isolate themselves, Europe was in the Age of Discoveries that would lead to the colonization of the world in the last two centuries. Morris thinks that the destiny of humankind was decided by nature even from the Stone Age. Nowadays, the natural conditions combined with sociological factors favor the rise of Asia as the hegemon who came back.

- Paul Varley - Cultura japoneză, Humanitas, București, 2017

- Curtis Andressen - A short history of Japan from Samurai to Sony, Allen and Unwin, Canberra, 2002

- W. G. Beasley - The Japanese Experience. A short history of Japan, The Orion publishing group, London, 1999

- Junko Habu - Ancient Jomon of Japan (Case Studies in Early Societies), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004

- Delmer M. Brown - The Cambridge History of Japan Volume 1, Ancient Japan, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993

- Keiji Imamura - Archaeological theory and Japanese methodology in Jomon research. A review of Junko Habu's Ancient Jomon of Japan, Department of Archaeology, The University of Tokyo, Anthropological Science, Vol. 114, 223–229, 2006

- J. Maringer - Dwellings in Ancient Japan: Shapes and Cultural Context, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1 (1980), pp. 115-123

- Junko Habu, Minkoo Kim, Mio Katayama and Hajime Komiya - Jomon Subsistence-Settlements Systems At The Sannai Maruyama Site, University of California, Berkeley, Anthropology Department, pp. 9-22

- Jon Turk - In the Wake of the Jomon: Stone Age Mariners and a Voyage Across the Pacific, Ragged Mountain Press, New York, 2006

- P. C. Swann- The Art of Japan From the Jomon to the Tokugawa Period, Greystone Press, New York, 1966

- Noritake Tsuda - A history of Japanese Art. From Prehistory to the Taisho Period, Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo, 2009

- Ryan W. Schmidt, Seguchi Noriko - Jomon Culture and the peopling of the Japanese archipelago: advancements in the fields of morphometrics and ancient DNA, Japanese Archaeological Association, 2014, pp. 34-59

- Ian Morris, De ce Vestul deține încă supremația. Și ce ne spune istoria despre viitor, Polirom, Iași, 2012

- Inazo Nitobe - Bushido. Codul Samurailor, Herald, București, 2013

- Okakura Kakuzo - The book of Tea, Penguin Classics, New York, 1906

- Ruth Benedict - The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture, Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, 2006

- Roger Blench, Laurent Sagart and Alicia Sanchez - The Peopling of East Asia Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics, Routledge, London, 2005

- Naoko Matsumoto, Hidetaka Bessho, Makoto Tomii, Joan Gero - Coexistence and Cultural Transmission in East Asia, Left Coast Press, California, 2011

- Gina Lee Barnes - China, Korea and Japan The Rise of Civilization in East Asia, Thames and Hudson, New York, 1993

- Gina Lee Barnes - State formation in Japan. Emergence of a 4th-century ruling elite, Routledge, London, 2007

- Keiji Imamura - Prehistoric Japan: New perspectives on Insular East Asia, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1996

- Mark Hudson - Ruins of Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Japanese islands, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1999

- Donald Denoon, Mark Hudson, Gavan McCormack, Tessa Morris-Suzuki - Multicultural Japan: Palaeolithic to Postmodern, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2001

- Kenneth Henshall - A history of Japan from Stone Age to Superpower, Palgrave Macmillan, New Zealand, 2012

- Ann Kumar - Globalizing the Prehistory of Japan. Language, genes and civilization, Routledge, New York, 2009