Hundred Days Offensive

The last battles of the war

8 August - 11 November 1918

The Hundred Days Offensive was the final series of battles in World War One during which the Entente forces launched a series of attacks against the German empire on the Western Front. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens the offensive pushed the Germans out of France, forcing them to retreat beyond the Hindenburg Line. The offensive ended the war with the Armistice of 11 November 1918. The term ‘Hundred Days Offensive’ does not refer to a single coordinated attack, but rather a rapid succession of battles that followed the Battle of Amiens.

1 of 5

The German Army was still a deadly enemy, and open warfare, desired for so long, was a cruel mistress, as the French had discovered in 1914.

2 of 5

The Battle of Amiens was the start of a 3-month long campaign that was one of the hardest ever fought by the British Army, the only compensation being the fact that they were winning. The fighting ranged from full-on assaults on layered defensive positions to bloody ambushes and the resulting frantic skirmishes. There are few more stressful military operations than an advance to contact through unknown country against a concealed enemy. The war was in its last stages but the casualty lists were mushrooming fast. The war had never seemed more painful.

3 of 5

The Amiens attack also illustrated the progress gained throughout the BEF in tactics and all-arms cooperation since the Somme offensive of 1916. The employment of aircraft in a ground-attack role, as well as on their normal artillery-spotting and reconnaissance duties, added extra bite to the offensive, while more extensive use of wireless helped improve battlefield communications.

4 of 5

After the Second Battle of the Somme, the Germans were forced all the way back to the Canal du Nord and the Hindenburg Line. In Flanders they were also forced to abandon their gains in the Lys area in order to shorten the line and conserve troops.

5 of 5

After the Hindenburg Line was broken, the German military and political leaders twisted and turned, with more than an eye on posterity, trying to avoid being held personally responsible for defeat. And as they did so, the war went on. But there was no chance of last-minute redemption for Germany: its effort to overcome the existing European order was doomed to failure.

Bolstered by their triumph during the Second Battle of the Marne, Entente officers began to plan a much bigger battle to capitalize on the German weakness. This was emphatically not the work of one man, or even of a small group of officers, but rather the synthesis of all that the British – aided by the French – had learned over the previous three years. It was a collegiate effort, marked by the wholehearted involvement of experts at all levels of the British Expeditionary Force and fully integrating all the new weapons into one ferocious methodology of modern war.

1 of 4

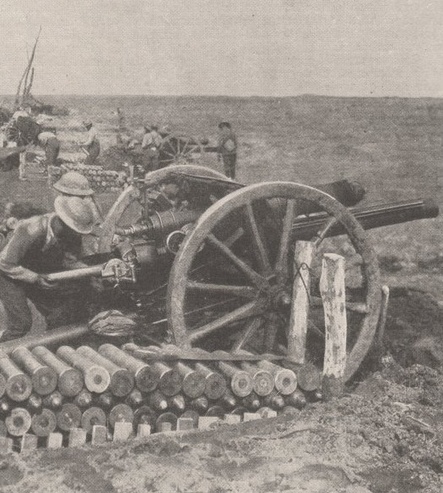

There was no longer any need to decide between counter-battery fire and a barrage: the BEF now had enough guns to allow for both with a comprehensive creeping barrage, forcing the Germans to keep their heads down as the British infantry approached.

2 of 4

The RAF, aided by flash spotters and sound rangers, had already managed to identify 504 of the 530 German guns. When the attack was launched, they would be neutralized by lashings of gas and high explosive shells to prevent them intervening as the infantry crossed No Man’s Land.

3 of 4

With the infantry came the tanks: 324 heavy tanks to squash the barbed wire and help crush any surviving German strong points; then 96 light Whippet tanks to create havoc behind the German lines; while a further 120 supply tanks were loaded with munitions to resupply the infantry in case of German counterattacks. This would be the biggest tank attack of the war.

4 of 4

The infantry themselves were unrecognizable from the warriors of 1915. They were fewer in number, but were covered by massed Vickers machine gun fire and carried their own Lewis guns, Stokes mortars and rifle grenades for immediate powerful support. Furthermore, they no longer advanced in lines, but in ‘short worms’ of about eight men feeling their way in ‘strings’ across No Man’s Land, preceded by well-trained scouts.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003