German invasion of Greece and Yugoslavia

German conquest in the Balkans

6 - 30 April 1941

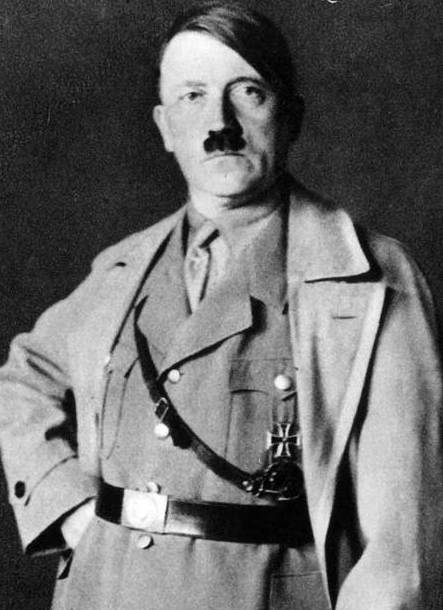

The Italian defeat at the hands of Greece forced dictator Benito Mussolini to ask his German ally, Adolf Hitler, for help. In Yugoslavia, a pro-Allied coup compelled the Germans to act against that country. The German war machine advanced quickly into Yugoslavia, crushing any resistance. In Greece, despite the efforts of the Greek and British armies, the northern line of defense was breached, and German troops then proceeded towards Athens. Greece and Yugoslavia remained under Axis occupation until 1944-45.

1 of 3

Hitler did not lose a moment in attacking Greece, which had been reinforced by British troops on the command of the War Cabinet. In retrospect, the Commonwealth expedition to Greece was one of the worst British blunders of the war, stretching General Archibald Wavell’s forces far too thin, which did not allow him to fight effectively in either Greece or Libya.

2 of 3

The Greeks and British – who did not coordinate their responses effectively, as the Greeks wanted to fight for Thrace, Macedonia and Albania – were outmaneuvered by swift Panzer thrusts around Mount Olympus, forcing the surrounded Greek Army to capitulate. The swastika was hoisted over the Acropolis.

3 of 3

After gallant Australian and New Zealand defense at Thermopylae, full of historical echoes of an earlier defense of Western civilization, some 43,000 British Commonwealth forces were evacuated from eastern Peloponnesian ports to the island of Crete and elsewhere, although little heavy equipment could be saved.

Prince Regent Paul of Yugoslavia joined the Axis and signed the Germany-Italy-Japan Tripartite Pact, causing outrage in Belgrade. Allied successes in Greece, Albania and Libya encouraged the eighteen-year-old Prince Peter II of Yugoslavia to declare himself of age and overthrow Paul the following night, assisted by the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Hitler was rendered incandescent with rage by this coup.

1 of 3

Hitler had been instructing the German High Command to draw up plans for the invasion of the Soviet Union. Suddenly, his right flank in southeastern Europe looked as if it might house a hostile Graeco-Yugoslav-British bloc. He ordered that Yugoslavia be subjected ‘with merciless brutality’ to ‘a lightning invasion’.

2 of 3

Yugoslavia had no realistic prospect of effective action against Germany and Italy. It was a weak regime governing a divided country of feuding nationalities, which coveted a piece of Greece for itself. It is correct that here too British diplomatic efforts had some American support, but it was surely unrealistic to expect Yugoslavia to take the only step likely to be useful: a quick invasion of Albania from the north to throw the Italians out of that colony entirely, then joining up with Greek forces. The coup in Belgrade appeared to give some retroactive validity to earlier British efforts, but by then it was entirely too late.

3 of 3

On the day of the coup in Yugoslavia, Hitler, as already mentioned, immediately decided to attack that country as well as Greece. He knew and was reassured by German diplomats that Yugoslavia had no intention of helping Greece; it was simply that many in Belgrade objected to joining the Axis and assisting an attack on their own southern neighbor which was certain to put them completely in Germany's power. But the German leader felt relieved not to have to make even for a moment the concessions he had promised.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms A Global History of World War Two, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994

- Andrew Roberts, The Storm of War A New History of the Second World War, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Williamson Murray, Allan R. Millett, A War To Be Won Fighting the Second World War, Belknap Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000

- Adrian Gilbert, Germany's Lightning War:From the invasion of Poland to El Alamein, 1939-1943, MBI Publishing Company, Osceola,WI (USA), 2000