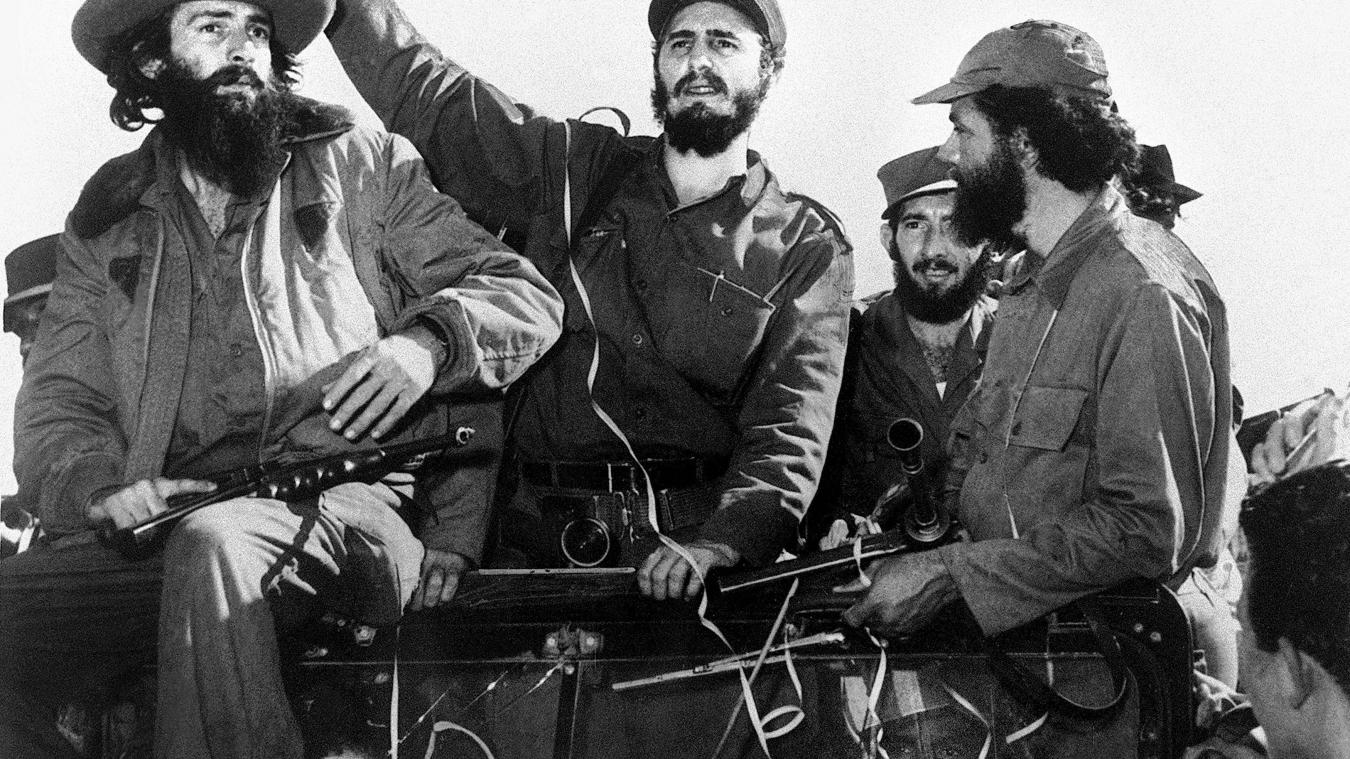

Cuban Revolution

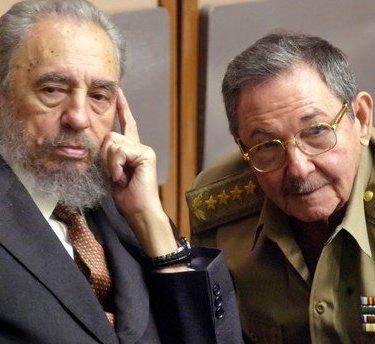

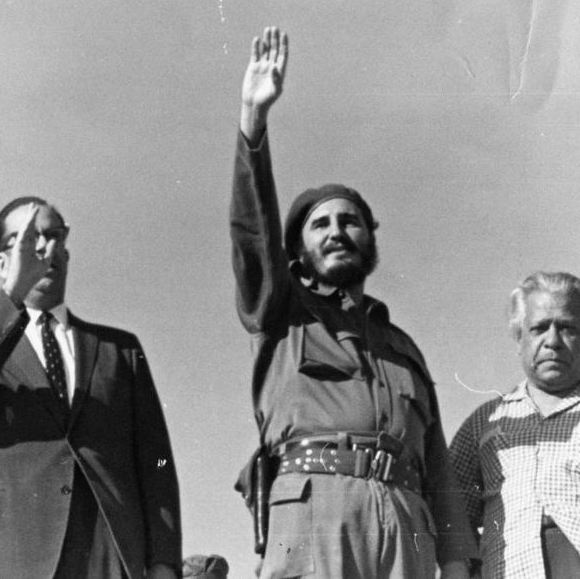

Fidel Castro becomes the new Cuban leader

The Cuban Revolution was an armed conflict perpetuated by Fidel Castro’s 26th of July movement against president Fulgencio Batista’s authoritarian government. The revolution began in 1953 and ended on the 1st of January 1959, when the rebels deposed Batista and replaced his government with a socialist one.

1 of 6

Castro’s plan for a Cuban revolution started poorly. On the 26th of July 1953, he led a band of 119 rebels in an unsuccessful attack on the Moncada army barracks in Santiago de Cuba, the most important military base in eastern Cuba at the time. Government troops captured Castro. He stayed in prison until Batista granted a general amnesty two years later.

2 of 6

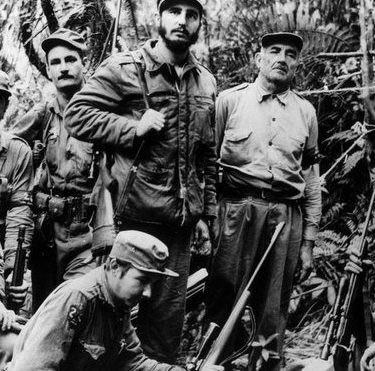

Upon his release from prison, Castro organized a small group of underground leaders in eastern Cuba. Castro moved to Mexico and used money from Cuban exiles in the United States to organize and train a small military force of 82 men. He called the force M (Movement)-26-7, after the date of the failed 26th of July attack on the Moncada barracks.

3 of 6

Castro returned to Cuba in a leaky yacht named the Granma. He landed at Cape Cruz in eastern Cuba. Batista’s army crushed the rebel force shortly after it landed. Castro and 11 others (including future commanders and revolutionary heroes Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, Fidel’s brother Raúl, and Camilo Cienfuegos) managed to escape into the Sierra Maestra range.

4 of 6

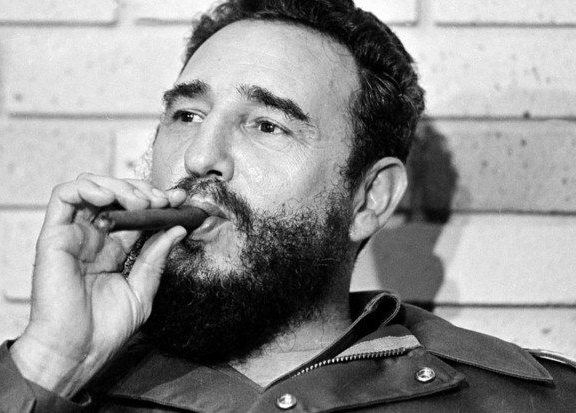

At first, Castro’s underground was unable to rally the local population to his cause; however, by the end of 1957, Castro’s revolution had captured the imaginations of the Cuban people. His rebels were carrying out guerrilla warfare—descending from the mountains to raid cane plantations and mines, and then hiding out in the mountains again. A radio station, set up at his headquarters in the Sierra Maestra, kept the people informed of the revolution’s growing strength.

5 of 6

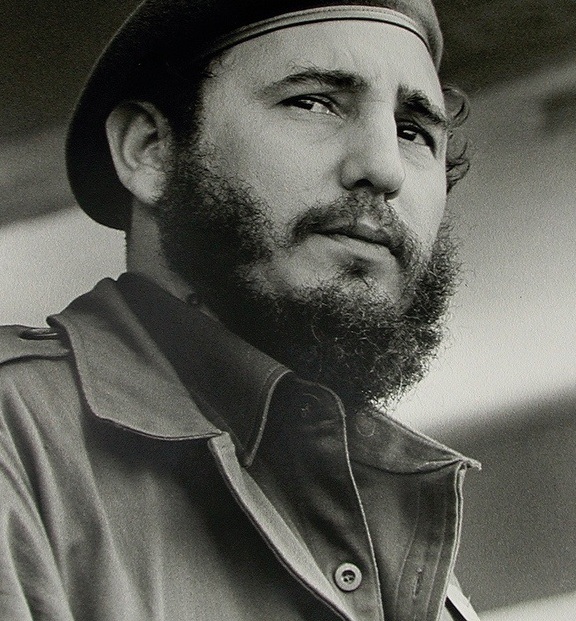

Castro had repulsed efforts by Batista’s army to push him from his Sierra Maestra stronghold. Raúl Castro controlled a second eastern front in the Sierra de Cristal. Together, the Castro brothers had Santiago de Cuba, the country’s second largest city, surrounded. Guevara and Cienfuegos were in charge of a third force in the Sierra del Escambray in central Cuba. By mid-1958, all three forces could hold their own in pitched battles against government troops.

6 of 6

Castro’s forces moved quickly out of the mountains. They scored major victories against Batista’s army in large cities: Santiago de Cuba, Bayamo, and Santa Clara. The armies of Guevara and Cienfuegos won victories in central Cuba and then swiftly moved towards Havana, compelling Batista to flee the country.

The stage for the violent upheaval was set by the existence of striking political, economic and social inequalities. More than one-third of the population was considered poor and lacking in social mobility. Coupled with this was the growth of a frustrated middle class whose rising expectations could no longer be met by a stagnant, sugar-based economy. A corrupt and repressive government supported by the United States had alienated its own people and spurred the growth of a Cuban identity and nationalism divorced from the United States.

1 of 2

Revolutionary struggles are rare throughout history. Successful revolutionary struggles are even more rare and they are the result

of many factors that come together in a given place at a given time. Cuba was no different.

2 of 2

The Cuban crisis during the 1950s went far beyond a conflict between Batista and his political opponents. Many participants in the anti-Batista struggle certainly defined the conflict principally in political terms, a struggle in which the central issues turned wholly on the elimination of the iniquitous Batista. But discontent during the decade was as much a function of socio-economic frustration as it was the result of political grievances. Batista's continued presence in power compounded the growing crisis by creating political conditions that made renewed economic growth impossible.

Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion was a failed military invasion of Cuba undertaken by Cuban exiles and sponsored by the US Central Intelligence Agency. It dashed all hopes that Cuba might stop its slide toward Communism.

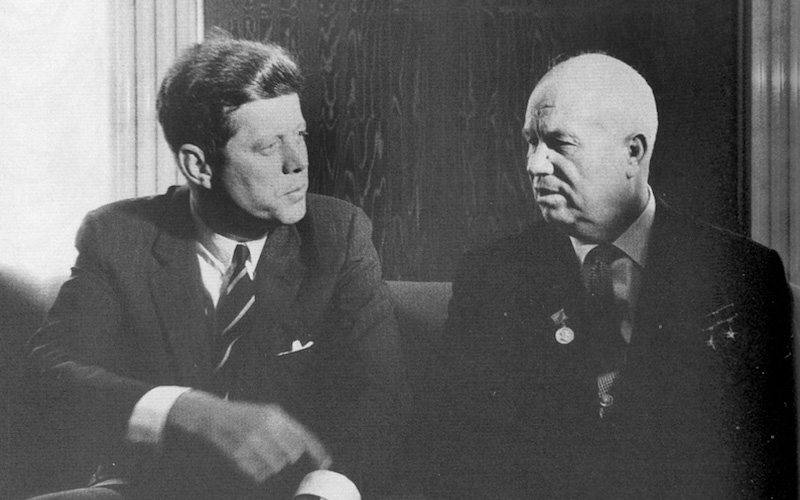

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis was one of the pivotal events of the Cold War. The world was brought to the brink of war when the Soviets, in retaliation for US missiles in Turkey, placed nuclear missiles in Cuba. The CIA found out about the Soviet activities in Cuba and president John F. Kennedy demanded the immediate withdrawal of the Soviet warheads.

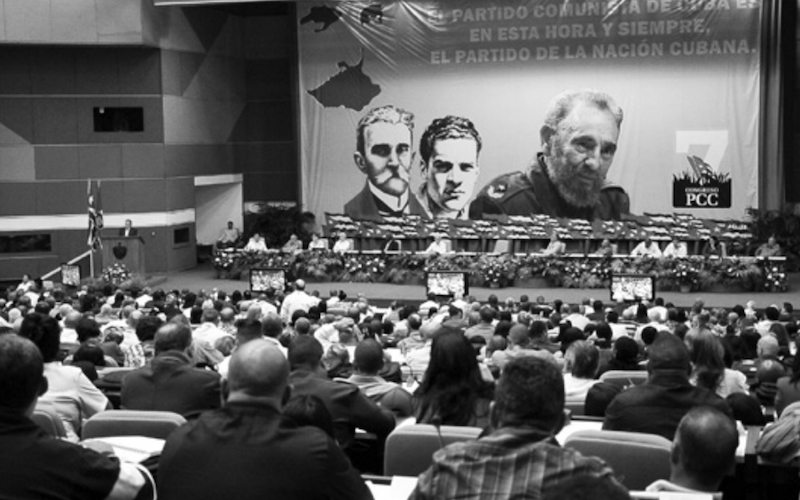

Cuba after the Missile Crisis

In 1965 Cuba officially became a communist state and started receiving aid from the Soviet Union. During this time, Castro's government used this aid to support guerrilla movements in Africa and Latin America. Because of the activities, Cuba's relationship with the United States remained hostile throughout the Cold War.

- Richard A. Crooker, Zoran Pavlovic, Cuba, 2nd Edition, Infobase Publishing, New York, 2010

- Clifford L. Staten, The history of Cuba, Palgrave MacMillan Publishing, New York, 2005

- Leslie Bethell (editor), Cuba: A short history, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993, Transferred to digital printing: 2007