Battle of Vittorio Veneto

Decisive Italian victory. Collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

24 October - 4 November 1918

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto was the last battle of the Italian Front during World War One. It was a decisive victory for the Italian forces, who managed to cause the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian army. The Italian victory contributed to the end of the war, less than 2 weeks later, and caused the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of the war.

1 of 3

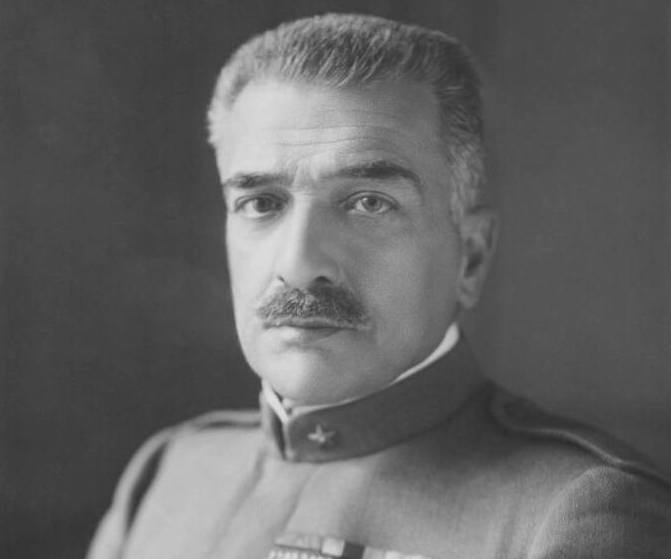

After the Italian victory at the Piave river in the spring, the Italian Chief of Staff, Armando Diaz, resisted appeals from the Entente commanders to launch any offensive before his army was ready.

2 of 3

By now the Italians had been augmented by significant French and British forces. Prime Minister Emanuele Orlando believed an attack now was essential in order to gain bargaining power at the conference table: all the signs indicated that the Austro-Hungarian empire was about to collapse.

3 of 3

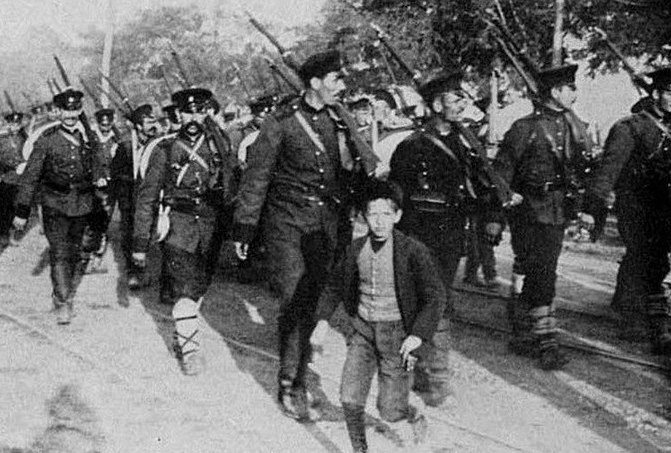

As the Entente army attacked at Vittorio Veneto, the Austrians broke and ran. A rout ensued, with mutiny and mass desertions by Serbian, Croatian, Czech and Polish troops. Mutiny also broke out in the Austrian navy and on the 3rd of November Austria signed armistice terms. The war in Italy was over.

In the spring and summer, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch asked Diaz to support the operations in France by attacking across the Piave. Diaz refused: his army was not ready. Orlando agreed, but changed his mind by mid-September when it became clear that the Entente breach of the Hindenburg Line meant that German defeat was close. His impatience mounted along with Entente pressure, and Orlando pressed Diaz to plan an attack.

1 of 3

Bulgaria’s collapse at the end of September and Ottoman Turkey’s imminent capitulation had shifted the balance: with their southeastern flank wide open and the Entente poised to attack, the Central Powers would not hold out much longer. If the Italians were left digging in for the winter while the rest of the Entente drove the Germans out of France and Belgium, their negotiating position would be feeble. If they were to win the territory pledged in 1915, they had to defeat the Austrians once and for all, knocking them out of the war.

2 of 3

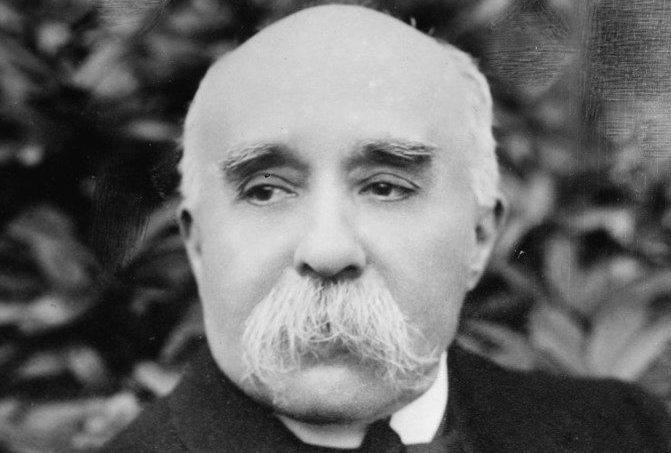

Diaz prepared to attack in the second half of October. His plan was ready by the 9th of October. When they met three days later, Orlando was smarting from his latest interrogation by Entente leaders in Paris; the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, easily irritated by the Italians, was galled by their inaction. Diaz issued the first orders for the offensive.

3 of 3

The Italians were worried to learn that Austria was working on a proposal to sue for peace on the basis of a unilateral retreat from Italian territory. This would steal their thunder, and Orlando – now so vexed by the Chief of Staff’s prudence that he wondered if he could replace him – telegraphed Diaz at once: ‘Between inaction and defeat, I prefer defeat. Get moving!’

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- Mark Thompson, The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919, Faber and Faber Limited, London, 2008