Asian and Pacific theatre of World War I

Entente conquest of German colonies in Asia and the Pacific

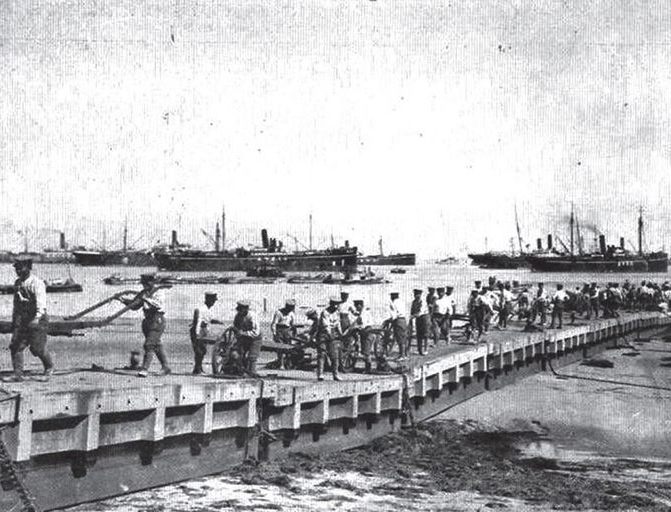

The Asia and Pacific theater of the Great War consisted of a series of naval battles and the Entente conquest of German colonies in the Pacific and China. The most significant land battle was the Entente siege of Tsingtao in China and the battles of Bita Paka and Toma in German New Guinea. The campaign is notable for Japanese intervention, on the Entente side. At the end of the war all German and Austrian possessions were lost.

1 of 5

Besides Tsingtao, the Japanese navy also used the opportunity of the war to seize the German Pacific islands north of the equator. Britain could hardly protest too strongly when its own dominions similarly seized the opportunity to further their colonial ambitions. New Zealand had occupied Samoa, and Australia laid claim to New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. But British anxieties were focused on the activities of the Japanese army on the continent of Asia.

2 of 5

Alone of the belligerent powers, Japan made sure that — for all the war's inbuilt pressures to the contrary — conflict served the purposes of its policy. For the political theorist, what is extraordinary about this outstandingly successful use of war for the achievement of political objectives was that it was carried out by a government that was weak and divided.

3 of 5

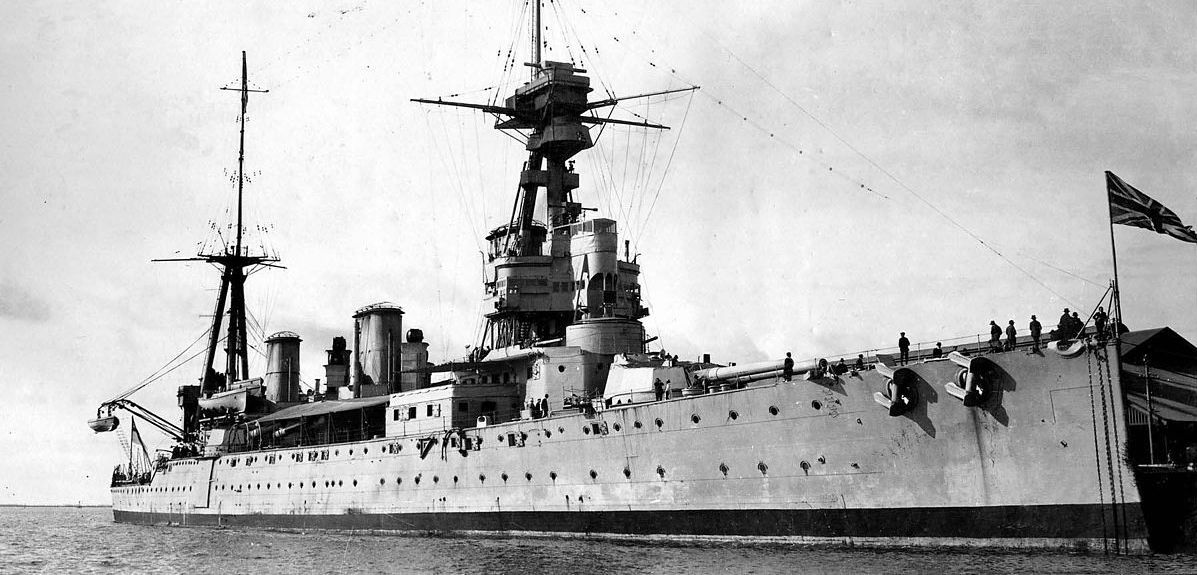

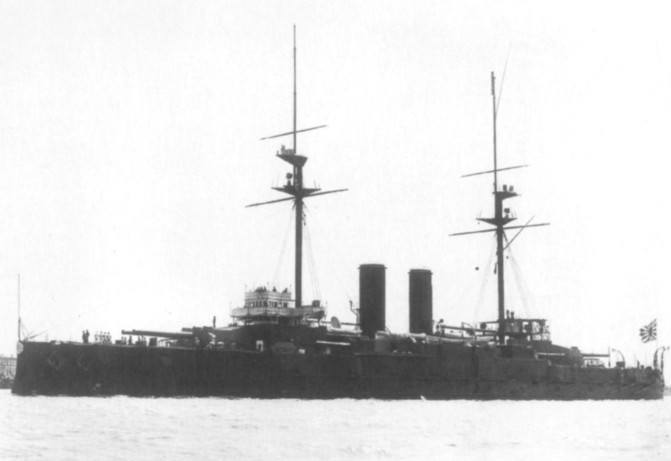

The military value of Japan's contribution to the Entente should not be underrated just because it remained limited by Japanese policy objectives. Japan entered the war as Britain's ally, not as a member of the Entente, and it did so as an Asian empire, not a European one. Therefore it was within the confines of the navy and of the Pacific that it elected to operate, and it is within these confines that its military value should be judged.

4 of 5

Japan’s initial assistance to the Royal Navy, which enabled the Chinese trade to resume within three weeks of the war's outbreak, was sustained throughout the war. In 1916 it was extended to the Indian Ocean, and in January 1917 to the Mediterranean. In 1918 the Japanese flotilla was the most efficient of the Entente naval units in that theater.

5 of 5

Russia too derived direct military benefit from its relationship with Japan; in addition to security on its eastern frontier, its arms purchases from Japan totalled 430,000 rifles and 500 heavy guns by the end of the first year of the war. Japan's military contribution can be even better appreciated if stated negatively rather than positively. Without it, the ability of Britain and Russia to concentrate on Europe would have been considerably diminished.

The Anglo-Japanese alliance of 1902 was designed by the British to deal with the balance of power in the Far East. It had never been intended as a weapon against Germany. However, in August 1914 the Admiralty’s anxiety about the defense of British trade in the Pacific caused it to change tack. The Japanese navy included fourteen battleships. The British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, asked the Japanese for limited naval assistance in hunting down German armed merchantmen.

1 of 4

In the minds of Australians the danger of invasion lay not just with Germany. Japan was seen as a threat which was as great and more immediate. Racism underpinned the fear. But Japan was Britain’s ally.

2 of 4

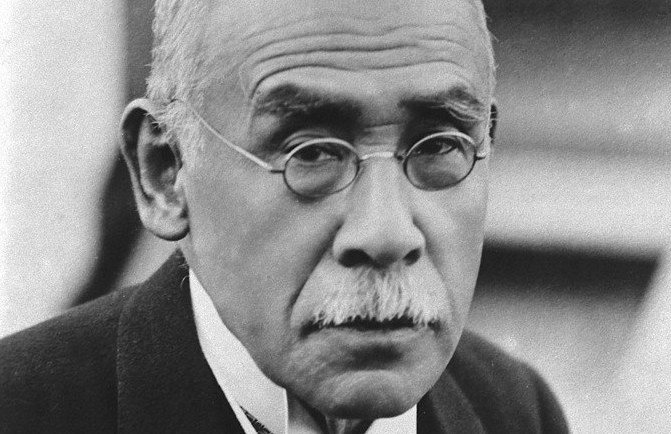

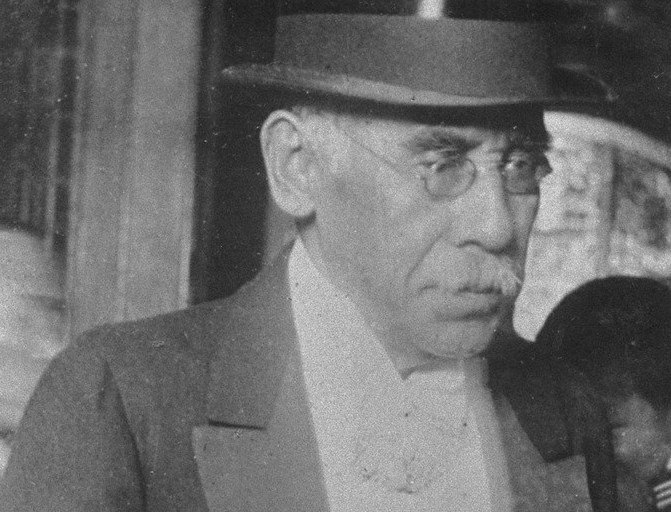

Most of the elder Japanese statesmen (the genro) and service chiefs believed that the Anglo-Japanese alliance had outlived its usefulness. Crucially, these were not the views of Kato Takaaki, the foreign minister, who had served as ambassador in London and who was an ardent anglophile. He wished to exclude the elders from government, to assert the cabinet’s control over the armed forces and to put parliamentary politics on a secure footing.

3 of 4

The war in Europe was, in the words of Inoue Kaoru, an elder Japanese statesman, ‘divine aid ... for the development of the destiny of Japan’. Like many others in Japan, as in Australia, Inoue interpreted international relations in racial terms. Just as the current war in Europe could be seen as a conflict between Teuton and Slav, so a future war would pit the yellow races against the white. Grey’s invitation was therefore a ‘one in a million chance’ to establish Japanese suzerainty in China, and therefore in Asia, while the European powers were engaged elsewhere.

4 of 4

Of all the world’s statesmen in 1914, Kato proved the most adroit at using war for the purposes of policy. Domestically he exploited it to assert the dominance of the Foreign Ministry and of the cabinet in the making of Japan’s foreign policy. Internationally he took the opportunity to redefine Japan’s relationship with China. In doing so he was not simply outflanking the extremists opposed to him; he was also honoring his own belief that Japan should be a great power like those of Europe. An essential aspect of that status was imperialism, as Britain itself showed.

- Hew Strachan, The First World War: To Arms (Volume I ), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998

- Hew Strachan, The First World War, Penguin Books, London, 2003