Second Battle of Ypres

Germans fight for control of the Flemish town of Ypres

22 April - 25 May 1915

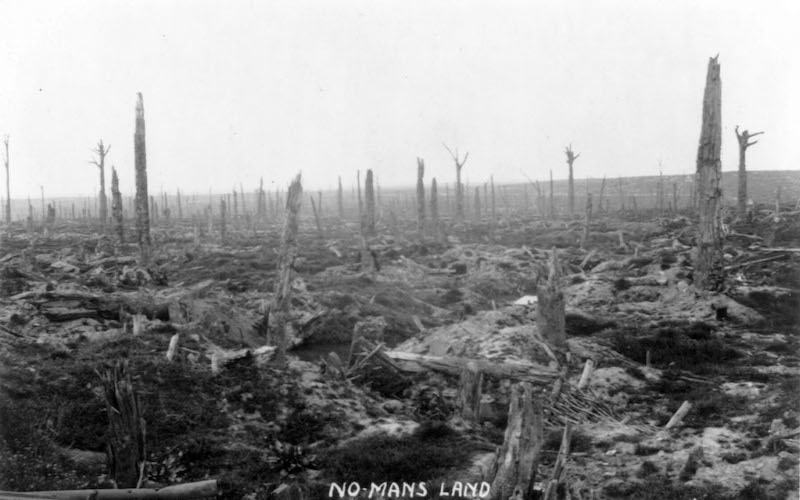

The Second Battle of Ypres was fought between the Entente forces and the German Empire on the Western Front of World War One. The battle was fought for the control of the strategically important Belgian town of Ypres, located in Flanders. It marked the first time the German Army used poison gas as a weapon on the Western Front. Although the Germans achieved an initial breakthrough, the British managed to hold the line.

1 of 4

Having bowed to a combination of pressure and circumstance in diverting resources to the Eastern Front, General Erich von Falkenhayn now attempted to maintain some degree of strategic surprise by covering the departure of his divisions from the Western Front. As he did not have the men or ammunition to launch a more conventional offensive, he sought to test the stalemate at Ypres by using the new German secret weapon of poisonous gas.

2 of 4

The very secrecy demanded by the presence of so many vulnerable gas cylinders in the front line, coupled with a lack of confidence in their own crude respirators, militated against any forceful follow-up by the German Fourth Army.

3 of 4

Gradually the British troops received gas masks which at first were all but useless, but later became far more effective. Gas became just another weapon in the huge arsenal of war. The British, for all their initial moral objections, would be using gas themselves before the year was out.

4 of 4

Before the Entente could launch their next offensive operations, the Germans – employing poison gas for the first time on the Western Front – attacked the northern flank of the Ypres Salient. This blow reflected all the confusion of strategic purpose that characterized Falkenhayn's term as Chief of the German General Staff. The Salient was important to both sides, but because Falkenhayn still accorded priority to the Eastern Front, the use of gas at Ypres was largely experimental.

General Falkenhayn had decided to renew pressure on the Ypres salient, partly in order to disguise the transfer of troops to the Eastern Front for the forthcoming offensive at Gorlice-Tarnow, and partly to experiment with the new gas weapon. The attack was to be a limited offensive, since Falkenhayn knew that his hopes of achieving decision in the west had to be postponed as long as Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff could effectively divert the movement of strategic reserves to the Eastern Front. Nevertheless, he hoped to gain ground and secure a more commanding position on the Channel coast.

1 of 4

Gas had already been used by the Germans, on the Eastern Front, at Bolimov, when gas-filled shells were fired into the Russian positions on the River Rawka west of Warsaw. The chemical agent, known to the Germans as T-Stoff (xylyl bromide), was tear-producing, not lethal. It appears not to have troubled the Russians at all; prevailing temperatures were so low that the chemical froze instead of vaporizing.

2 of 4

By the time of the Ypres attack the Germans had a killing agent available in quantity, in the form of chlorine. A ‘vesicant’, which causes death by stimulating overproduction of fluid in the lungs, leading to drowning, the material was a by-product of the German dye-stuff industry, controlled by IG Farben. The company commanded a virtual world monopoly in those products.

3 of 4

Carl Duisberg, head of IG Farben, had already rescued the German war effort from collapse by his successful drive to synthesise nitrates, an essential component of high-explosives obtainable organically only from sources under Entente control.

4 of 4

Simultaneously Duisberg was cooperating with Germany's leading industrial chemist, Fritz Haber, head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, to devise a means of discharging chlorine in quantity against enemy trenches. Experiments with gas-filled shells had failed - though, with a different filling, gas shells would later be widely employed. The direct release of chlorine, from pressurised cylinders, down a favorable wind, promised better.

The First Winter

During the first winter of the war, after heavy fighting in the previous months, the front stabilized. A series of trenches and fortifications were built by both sides all along the front. During this time the French launched a series of attacks against German positions, attacks which would ultimately prove to be costly in terms of casualties and tactically indecisive. A curious anomaly happened in some sections of the front during...

Battle of Neuve Chapelle

At the battle of Neuve Chapelle the British mounted an offensive against the German in the Artois region of France.

1915 Spring Offensives

During the spring and summer of 1915 the Entente forces, under the command of French General Joseph Joffre, launched a series of attacks against the German lines. These attacks would ultimately prove costly failures in terms of human lives, while failing to capture any significant portion of the front from German hands.

1915 Autumn offensives

During the autumn of 1915 the French and British organized a series of new offensives against the German army designed to break the German lines. However, because they lacked sufficient artillery ammunition and could not move the reinforcements quickly enough these offensives were doomed to failure, especially when considering the well organized German defense.

- Peter Hart, The Great War: A Combat History of the First World War, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey, Hew Strachan, The First World War: The War to End All Wars, Osprey Publishing. Oxford, 2003

- John Keegan, The First World War, Random House UK Limited, London, 1998