History of Rockets

Rockets, those elegant and powerful cylinders, are what guide people and robotic spacecraft into space. They also traditionally serve as propulsion systems for spacecraft post-liftoff so the satellite, Space Shuttle, etc, can reach its destination. Rockets represent some of mankind’s most advanced technological creations. From their relatively humble beginnings in the realm of ancient firecrackers to the larger-than-life Saturn V, rockets may have changed in scale and application but they still rely on the same basic principles of physics.

1 of 4

The spacecraft that rockets carry into orbit around Earth or beyond have their own power requirements. And given the distances that spacecraft must travel, calling home is a lot more difficult than a long distance phone call. Communications between space and Earth require an advanced network of radio antennae and, fortunately, such a system already exists today.

2 of 4

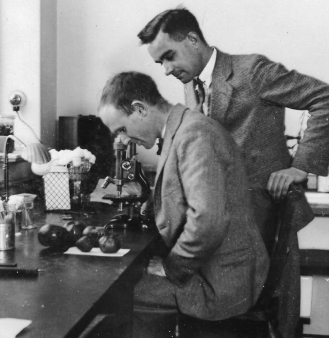

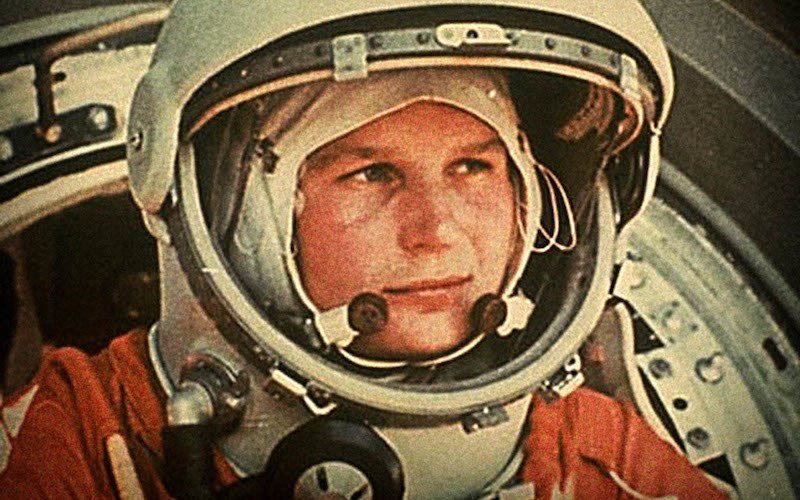

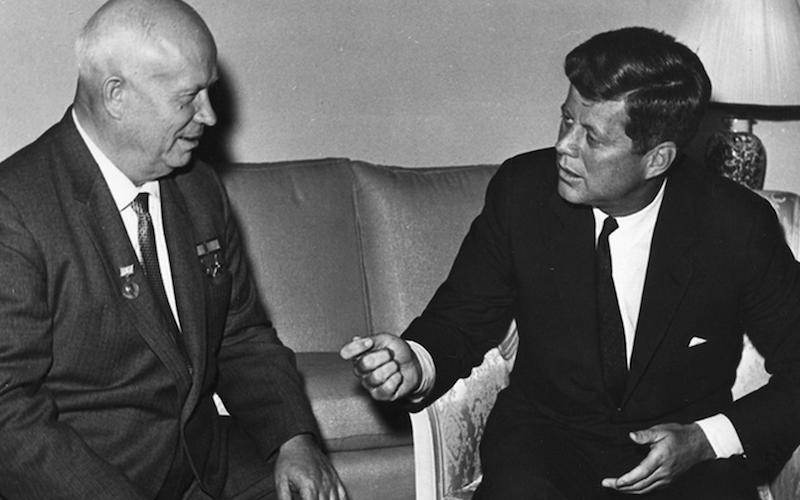

Two men have become synonymous with the start of the Space Age. Both were fortunate to survive the Second World War. Separated by the Iron Curtain, they never met, but they dreamed the same dreams, were both victims and beneficiaries of politics and both achieved remarkable things. The first of these great pioneers was Wernher von Braun, who was born in Germany just before the First World War. The second was Sergei Pavlovich Korolev. Korolev dreamed of flight, voraciously reading the exploits of aviation pioneers.

3 of 4

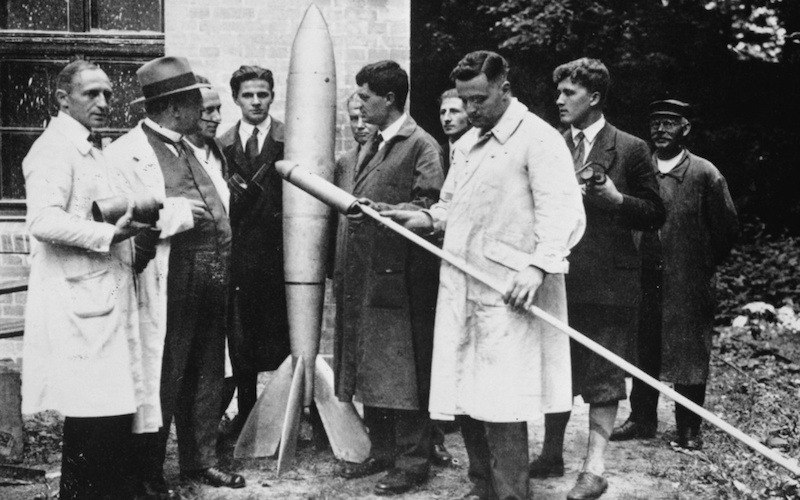

The men responsible for reaching space and landing on the Moon took their first steps toward that goal during the 1930s. Parallel developments in the United States, Germany, and Russia would challenge their best scientists and engineers to be the first to solve the problems of rocket propelled flight. Though these men dreamed of using rockets to explore space, their respective governments directed their work at providing new weapons for war.

4 of 4

In the 20th century it finally began to seem that Mankind’s long-held vision of traveling in space could become a reality. Yet despite the peaceful ambitions of the early pioneers of rocketry and spaceflight, the technology needed for such an event was developed initially to produce weapons of war.

The modern rocket was a long time coming. The ancient Greeks invented a rocket-like device, while the ancient Chinese actually used rockets for entertainment and, later, for warfare. By the 14th century rockets were known in Asia and Europe. In the 18th century the Indians used rockets against the British. At the beginning of the 19th century rockets are used militarily in Europe for the first time. During World War 1 rockets were mounted on planes for the first time.

1 of 7

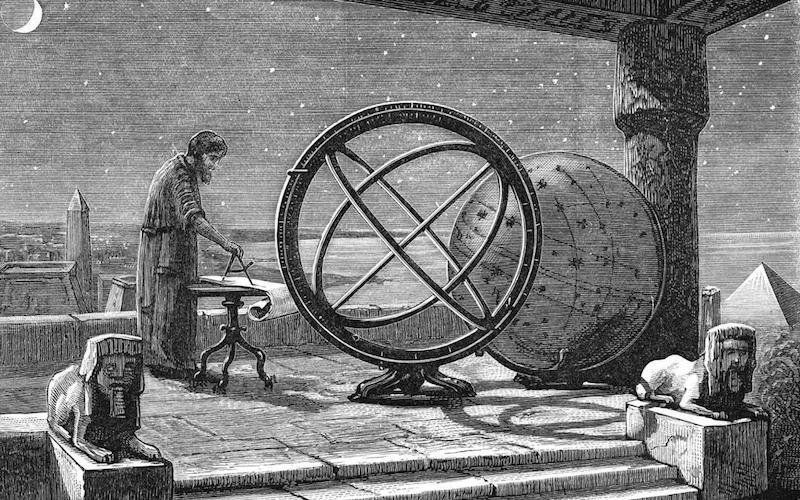

The first known device similar to a rocket dates back to the first century CE. It was then that Heron, a Hellenistic Greek from Alexandria, invented a steam-powered engine called the aeolipile, which was similar to a rocket engine. Heron described the principles of reaction motion in his treatise, Pneumatics. However, in spite of what the ancient Greeks and others understood in theory and created in prototype, apparently no practical use was made of the principle.

2 of 7

Fireworks and firework rockets were developed by the Chinese and their neighbors for fun, spectacular displays, and religious rituals often associated with the time of year crops were planted or reaped. This appears to be the first widespread use of the reaction principle for propulsion. The Chinese developed festival fireworks around A.D. 600 while rocket-powered weapons followed around A.D.1000.

3 of 7

The Chinese used rockets for warfare during the 12th century CE. The first “propellant” (a mixture of saltpetre, sulfur, and charcoal called black powder) had been in use for about 1,000 years for other purposes. As is so often the case with the development of technology, the early uses were primarily military. The first confirmed use of war rockets was in 1232, when China used them

against the Mongols.

4 of 7

The Mongols, used rockets against Poland in 1241 and against Baghdad in 1258. Muslim armies used rocket-powered projectiles during the Seventh Crusade. By the end of the thirteenth century, rocket weapons were known in Japan, Java, Korea, and India. Knowledge of rocketry spread quickly throughout Asia and into Europe at the same time. The Italian word rochetta was introduced. This is the earliest use of the word “rocket” in Europe.

5 of 7

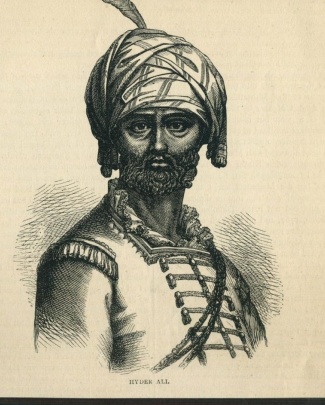

Hyder Ali (1781) and Tipu Sultan (1792–1799) used advanced war rockets against the colonizing British in India. It was the success of the Indian war rockets that inspired Colonel William Congreve to develop a new war rocket for the British. Congreve’s rockets used black powder, had iron casings, and 4.9-m guide stick for stability. They had an average range of about 2,800 m. These rockets were used as signals and as artillery. There is a phrase in the national anthem of the United States about the “rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air” that refers to England’s use of Congreve’s rockets against America during the War of 1812.

6 of 7

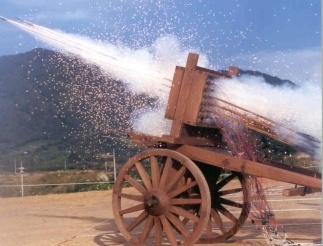

Powered by black powder charges, rockets served as bombardment weapons, culminating in effectiveness with the Congreve rockets

of the early 1800s. Performance of these early rockets was poor by modern standards because the only available propellant was black powder, which is not ideal for propulsion. European and U.S. armies quickly adopted Congreve-style rockets and worked to improve them. The stick-less Hale rocket (1840s) had a greater range and was far more accurate Military use of rockets declined until 1936 because of the superior performance of guns.

7 of 7

Claude Ruggieri was the royal pyrotechnician of France in the 1820’s. He began experimenting with launching live animals in rockets, returning them unharmed to the ground by parachutes. After successful experiments with mice and rats, he announced his plans to build a giant combination rocket that would carry a full-size ram aloft. Immediately after this announcement, Ruggieri received an offer from a young man who volunteered to take the place of the animal. A date for the big event was advertised. The police forbade the experiment.

Astronomy in the Ancient Times

Astronomy is a science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. Humanity has studied astronomy since ancient times. Astronomy, as an orderly pursuit of knowledge about the heavenly bodies and the universe, did not begin in one moment at some particular epoch in a single society. Every ancient society had its own concept of the universe (cosmology) and of humanity's relationship to the universe. In most cases, these concepts were...

Astronomy in the Modern Times

Space Race

Space exploration and the Cold War

Space Agencies

Science fiction and space exploration

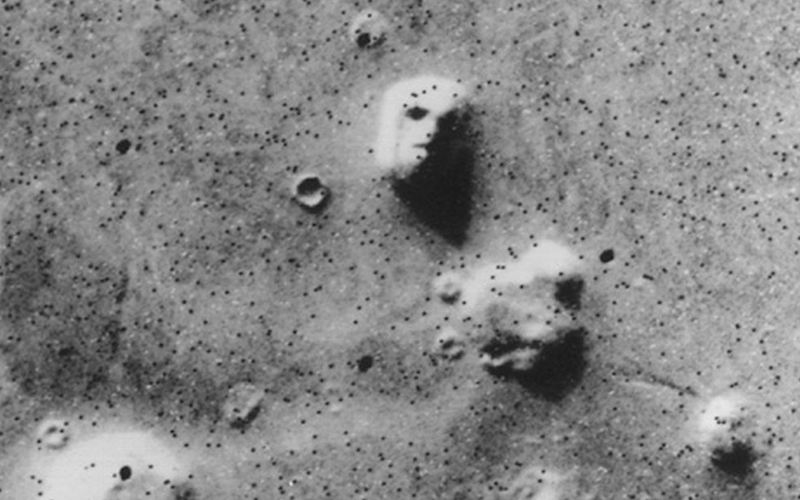

Exploration of Mars

Exploration of the inner solar system

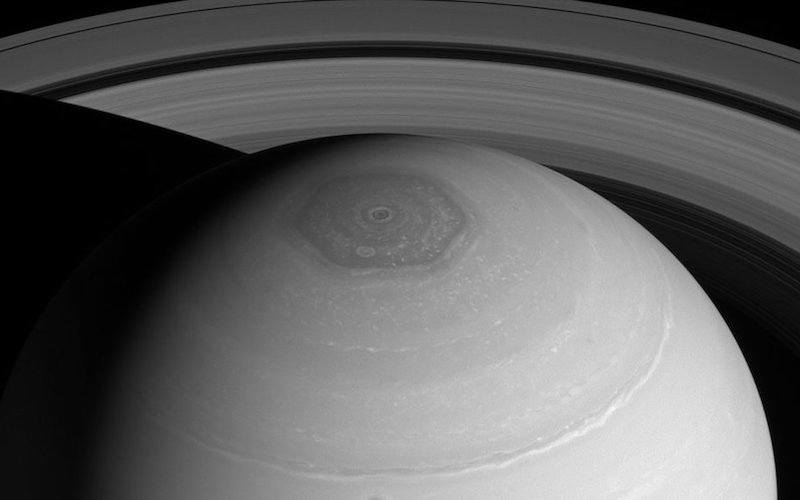

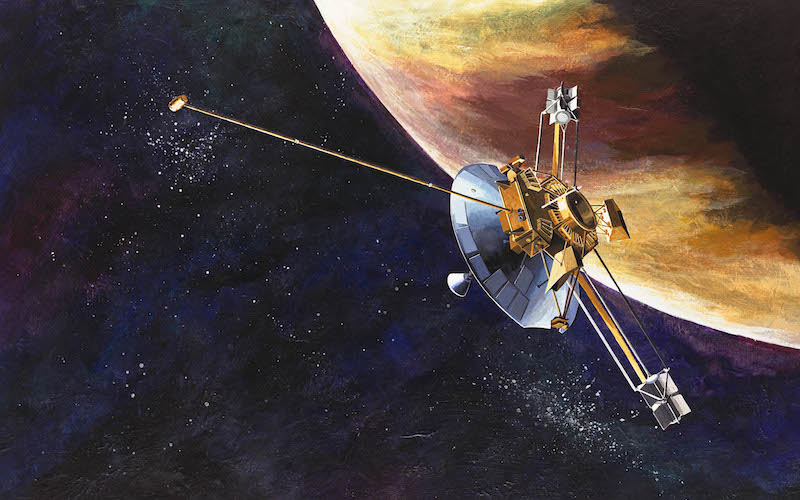

Exploration of the outer solar system

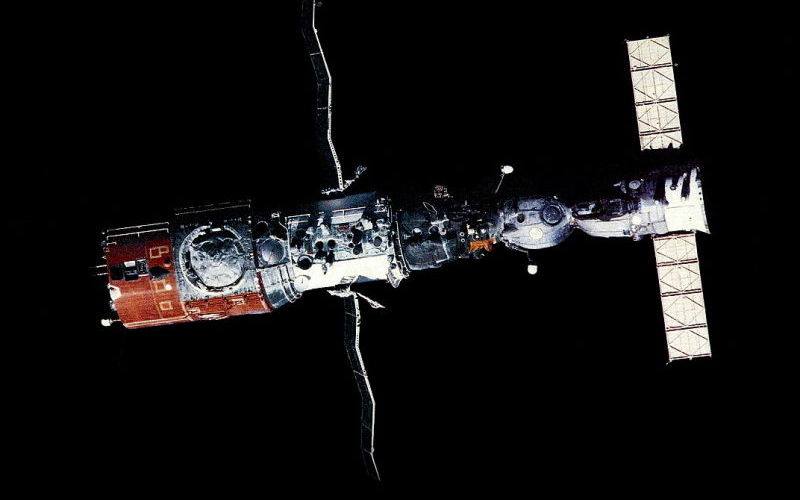

Modern orbital space exploration

History of Satellites

One of the most dramatic moments of the twentieth century occurred on October 4, 1957. The Soviet Union sent a small shiny sphere with four long antennas into space. They called it Sputnik I. Sputnik is a Russian word that means “traveling companion.” The satellite traveled so fast that its ballistic flight continued all the way around Earth.

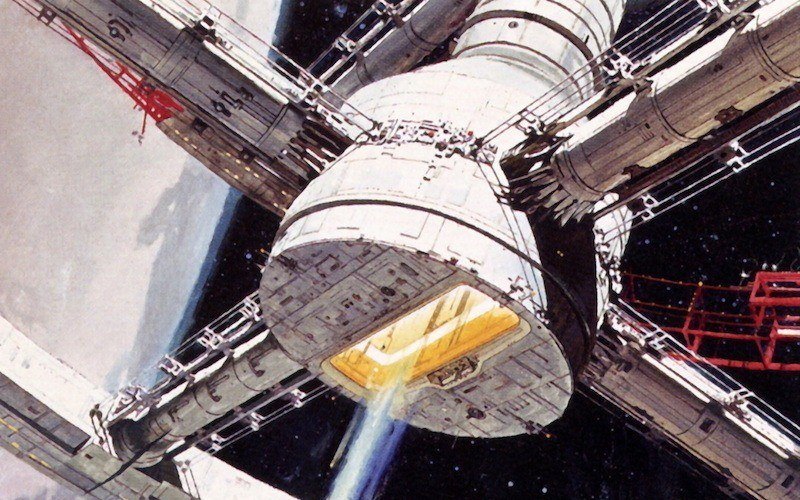

The Future of Space Exploration

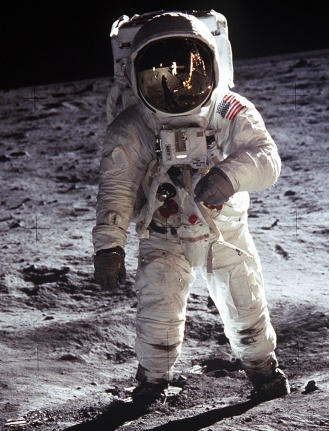

While the current lunar exploration initiative has been justified as a “stepping stone” toward Mars, human missions to Mars represent a major step up in complexity, scale, and rigour compared to lunar missions.

- Brian Bonhomme, Russian exploration, from Siberia to space: A history, McFarland & Company, Inc., Publisher, Jefferson, North Carolina, 2012

- Cynthia Phillips, Shana Priwer, Space exploration for dummies, Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana, 2009

- Erik Gregersen, Unmanned space missions: An explorer’s guide to the universe, Britannica Educational Publishing in association with Rosen Educational Services, New York, 2010

- James A. Dator, Social foundations of human space exploration, Springer Science+Business Media,New York, 2012

- Peter Jedicke, Great moments in space exploration, Infobase Publishing, New York, 2007

- Ron Miller, Space exploration, Space innovations, Twenty-First Century Books, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2008

- David Whitehouse, One small step: The inside story of space exploration, Random House Publisher Services, New York, 2009

- Marianne J. Dyson, Twentieth century space and astronomy: Decade by decade, Infobase Publishing, New York, 2007